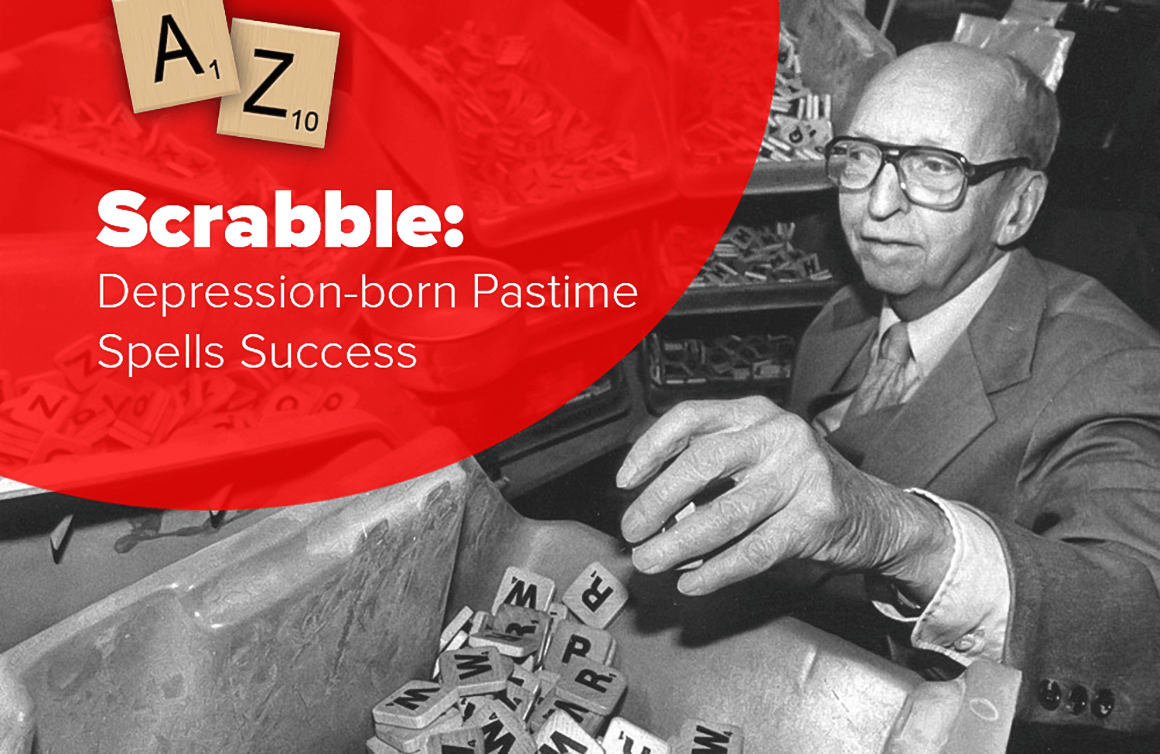

In 1931, Alfred Butts, a 32-year-old architect in New York, lost his job. He tried various ways of generating income, including writing, painting, and making art prints. Finally, he decided to try designing a game. Competitive Scrabble player and former Wall Street Journal writer Stefan Fatsis researched the Alfred Butts archive for his 2001 book Word Freak. Fatsis discovered that Butts believed historical games, based on words, had since inspired “nothing better than anagrams.” Determined to change this, he set about designing an entertaining word game.

Butts wasn’t much of a game player. But he was meticulous and endowed with tenacious qualities held by most contemporary game lovers. He found inspiration in Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Gold Bug, in which the narrator solves a cypher (and finds pirate treasure) by counting the frequency of symbols and comparing them to the frequency of letters in printed documents. But Poe’s breakdown of letter frequency was way off. Butts was determined to find “a mixture” of letters “proportioned that the individual letters will occur in the same frequency as they do in normal word formation.” He counted letters in printed documents and recorded his results in handwritten spreadsheets. He drew from several sources including the New York Times and The Saturday Evening Post. After weeks of tabulating, he determined his letter frequency and decided that the game should contain just 100 letters. He printed his game boards on an architect’s blueprint machine and began to sell the game, which he named Lexico.

Meanwhile, he and his wife continued to play and refine the basic game, in hopes of better sales. By 1938, satisfied with his fine-tuning, Butts renamed the game to Criss Cross Words and continued to build and fill orders by hand. Though rehired by his former architectural firm, he peddled his blueprinted game for the next 9 years. Unfortunately, he wasn’t a very good marketer.

James Brunot approached Butts in 1947, offering him a deal. Brunot would manufacture the games and pay Butts a small percentage of sales. Tired of filling orders and making and assembling games, Butts agreed. Brunot tweaked the game design just a little more and changed the name to Scrabble. Slowly, Scrabble began to sell.

By early 1952, sales of the game amounted to about 200 sets per week. Returning from a week’s vacation, Brunot and his wife were stunned to find orders for 2500 sets, followed by 3000 orders the next week. Apparently, the chairman of Macy’s, Jack Straus, had played Scrabble during a vacation and was angry, upon his return, that his store didn’t carry it. By March of 1953, Brunot had to farm out manufacturing of Scrabble to production giant Selchow & Righter. Sales of Scrabble continued to grow and both Brunot and Butts reaped the benefits. Scrabble’s story is one of innovation, perseverance, refinement, and learning the value of marketing—from words to riches!

Note: If you buy something using the eBay link in this story, we may earn a small commission. Thank you for supporting independent toy journalism!