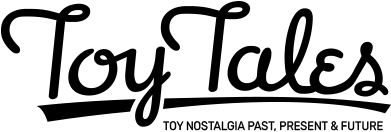

How do you describe your collection?

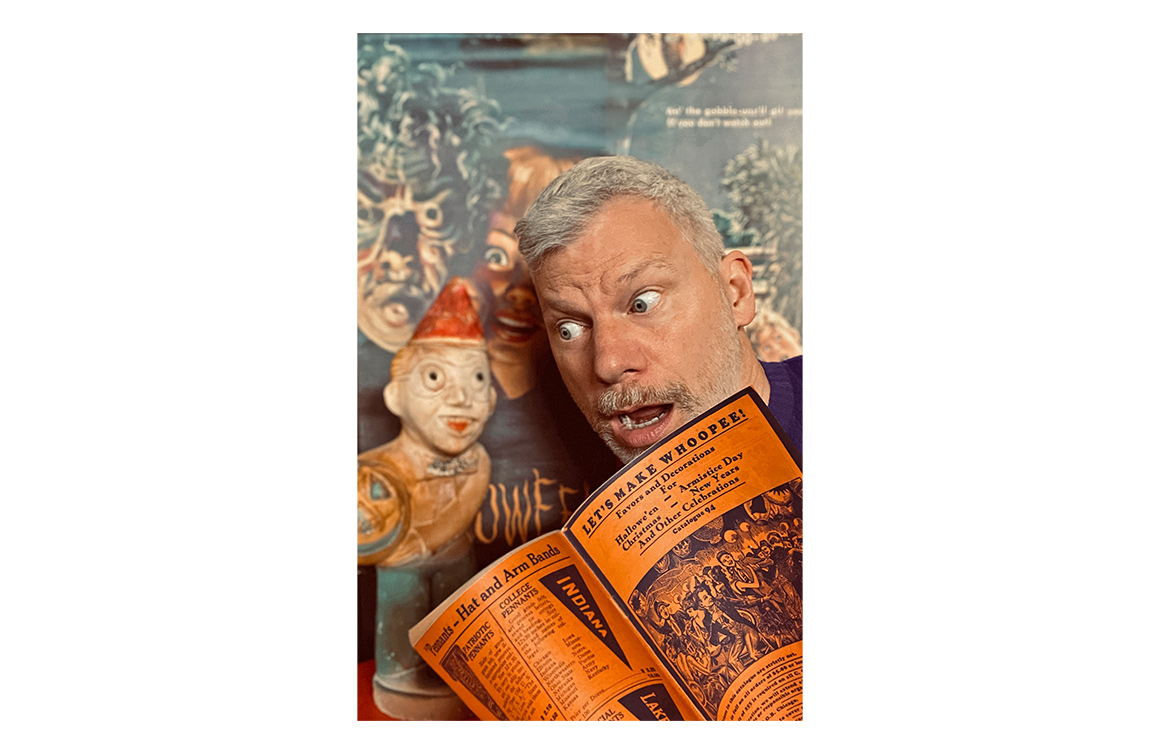

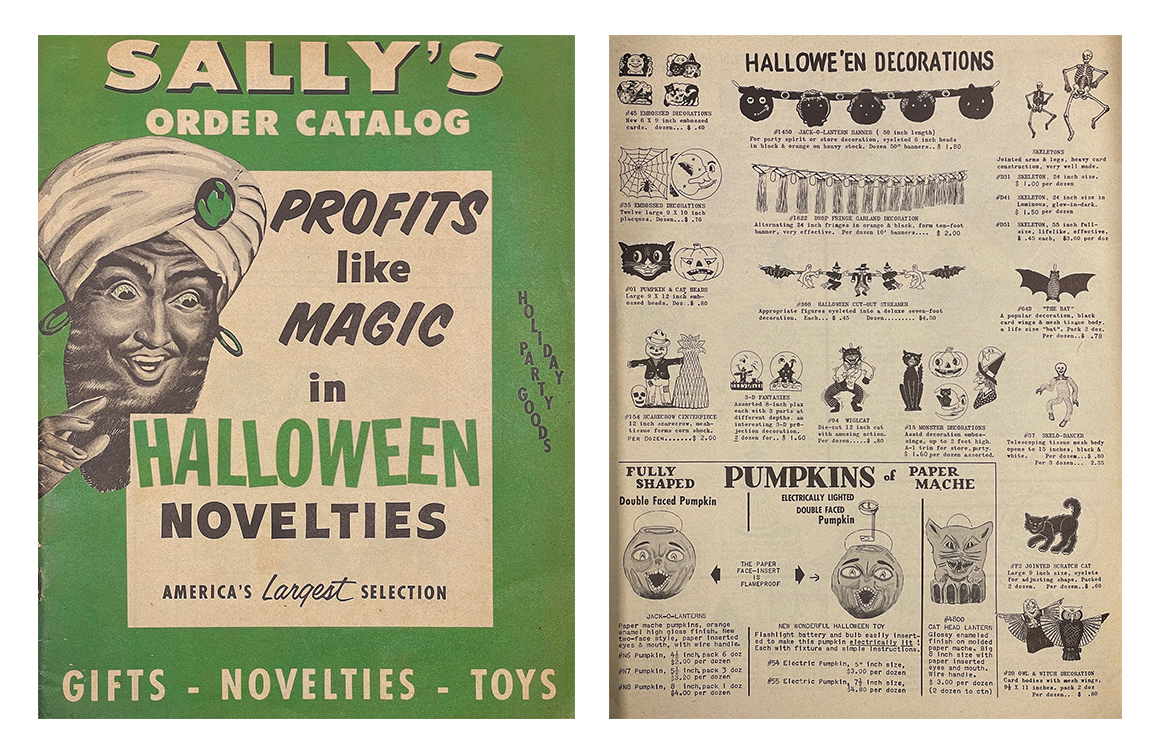

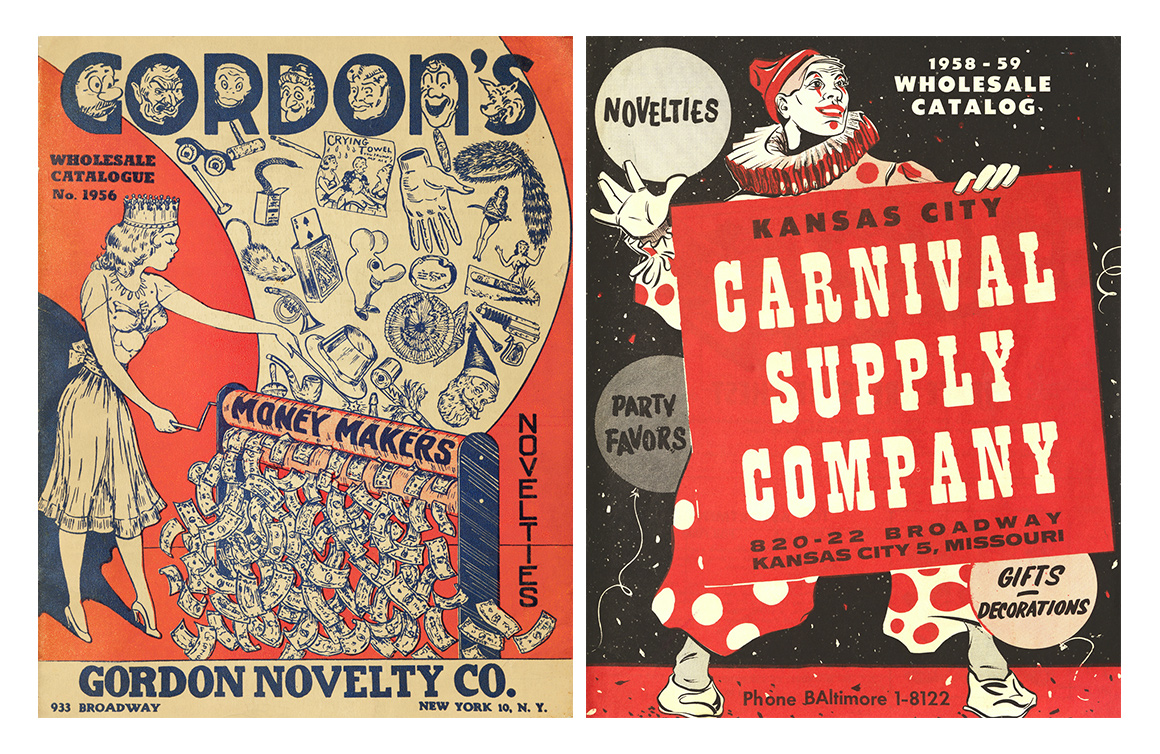

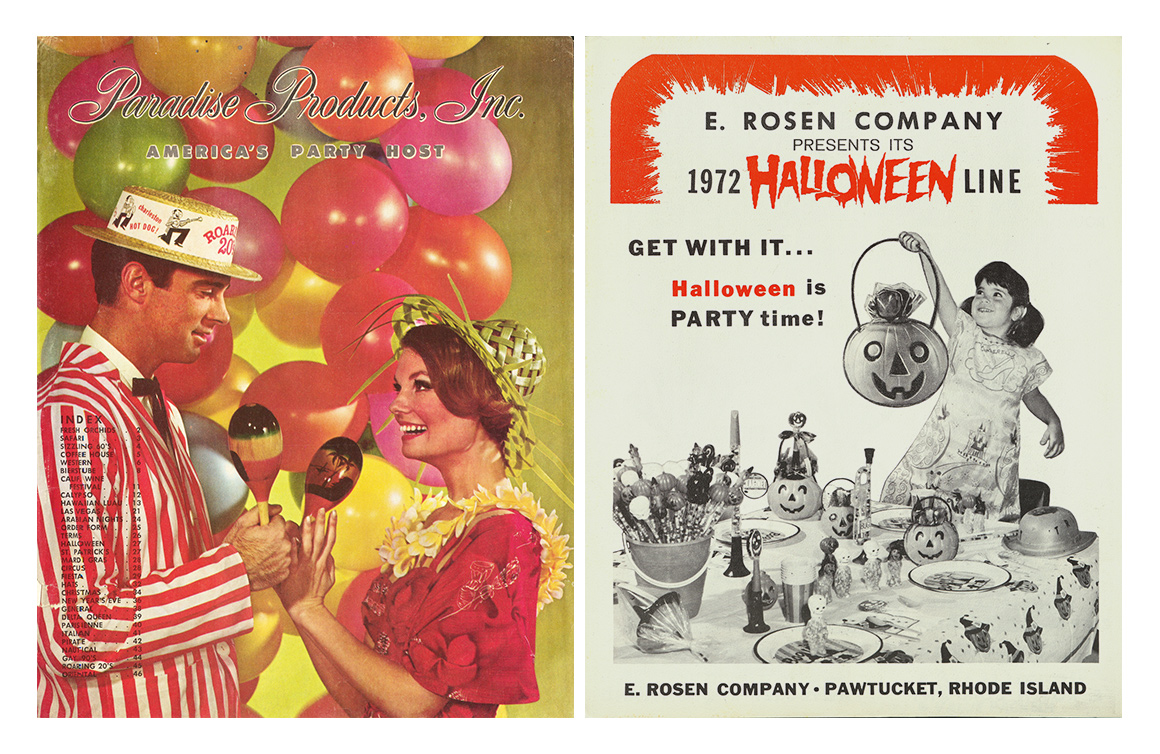

I collect vintage novelty and favour supplier catalogues — generally dating from 1900 to 1979 — that promote the quirky items we would consider irrelevant in day-to-day survival. Think pages of charms, costumes, decorations, fake flowers, gambling supplies, jokes, ornate housewares, toys, etcetera.

To date, shelf copies in my collection are minimal at 245, though expanding, and there are relevant samples from 280 catalogues (authoritative surrogates) obtained through online searches and personal visits. I like to think of those numbers in perspective. While I am in complete awe of larger collections like 41,000+ catalogs in the Lawrence B. Romaine Trade Catalog Collection, UCSB Library, my tiny library assures relevancy to my focus.

Dating some catalogues is a challenge. One of the oldest print items here is circa 1909. This is a catalogue for customers of New York store B. Shackman & Co with entries for candy containers, figurines, noisemakers, and similar objects. One of the most recent is a 1976 catalogue from Sally’s aimed at wholesalers — distributors, vendors, jobbers, resellers — to outfit, for example, entertainment venues such as carnivals with objects including animated clocks, Christmas ornaments, rubber masks, salt and pepper shakers, wall plates, and more.

When and why did you start your collection?

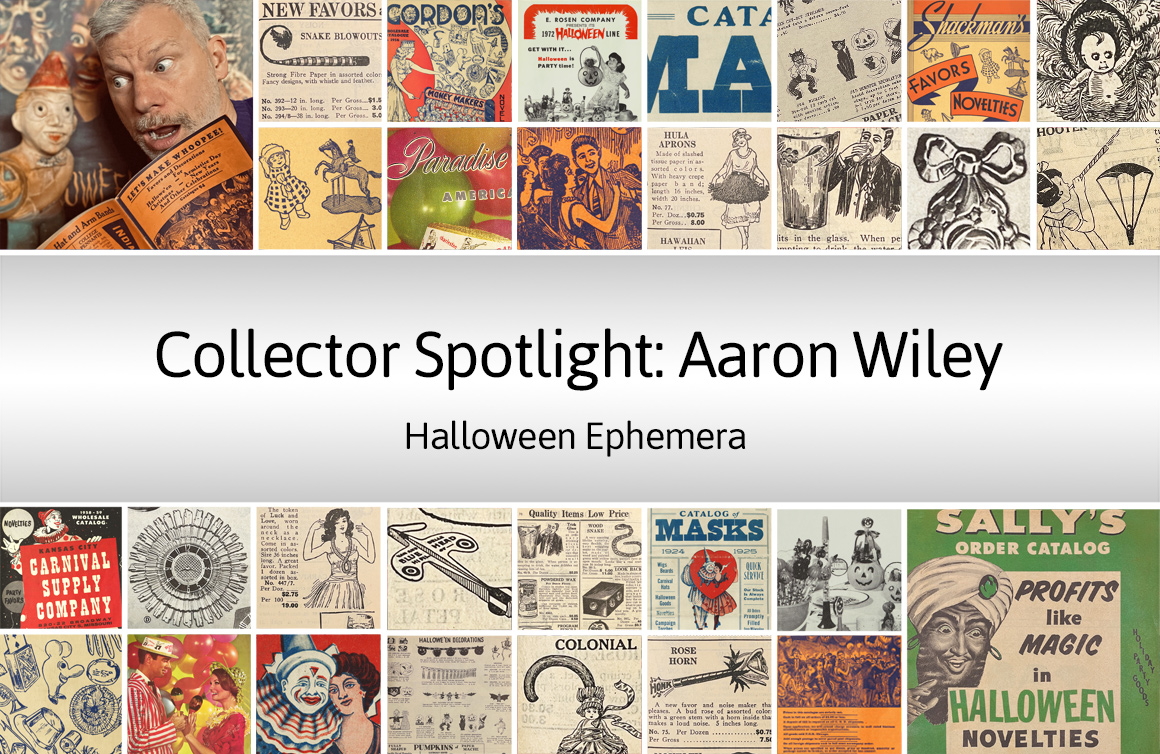

Collecting catalogues is a relatively recent venture for me and is an extension of other interests. Since childhood, I was fascinated with creativity in holiday kitsch, but as a working adult in the 1990s, I began a bargain collection of vintage holiday objects as a tonic to a grim job market.

Sometimes industrializing my own versions at a small scale, my curiosity grew for the history of novelty manufacturing. I started collecting old publications as my guidebooks, and that interest expanded into a library when, like first-hand accounts, the catalogues revealed stories of product availability unseen elsewhere.

As for catalogues here, there is a bit of a progression. At first I collected Dennison publications — predominantly 1910s to 1930s — featuring their products along with suggestions and prices. Later a copy of Ben Truwe’s book 55 Catalogs from the Golden Age of Halloween set the real pattern for a catalogue collection. Sensing that I had ignored a wider variety of vendors, I started digging through general merchandise catalogues. It was a real eye-opener to find niche collectibles in places such as teacher supply catalogues and in catalogues for the home like Sears, Roebuck & Co.

Collecting unlocked new possibilities for me.

I had an associate’s degree in web design and development and worked in Seattle when the technology bubble burst in the late 1990s. I was looking for a way to get through a rough job market — it was a tough time. I wondered what I could do that was just for fun and to revisit the joys I felt as a kid. For me, that was the holidays.

I started studying modern guidebooks and learning from the images. I then realized that I wanted to see these things in my hand — I wanted to understand their construction and how the pieces came together. For example, 12-piece lanterns that fold flat but could also unfold into three dimensions. I thought it was incredible that people were doing that. I began collecting objects and was a bit of a completionist. I started to understand the materials that were available during that era and wanted to know more. My catalogue collection has grown ever since.

In collecting the catalogues and expanding my view, I wanted to document and preserve the information I was learning. I earned a Master’s degree in Library and Information Science and published two volumes of Halloween Retrospect. I did it for myself as a sort of companion to my collection. I guess it’s part of my exit strategy — wherever this collection ends up, these books explain the objects and my research into them.

How do you display and store your collection?

This small library is in a home office. There, among Halloween collectibles, are shelves devoted to catalogues representing the products that surround them.

I realize it’s an amateur archive, but I try to implement institutional-type care and caution — like tracking temperature, humidity, and other external factors. When the catalogues arrive, they go to an examination station outside the office and receive their own container. Next, they move to a scanner area, eventually making it to shelves organized by company name and date. Though I have yet to utilize a full-scale archive or library management system, I’m making sure the content is recorded with high-resolution imagery, and that pertinent information is entered into a spreadsheet. I want each catalogue to have authority as a primary source.

All of this creates new challenges. Although I collect these as valuable to research, I realize incidental content outside of my interest is invisible to others who could use it. I hope one day to connect with collectors similarly involved with catalogues who see possibilities of catalogue-data exchange. Or perhaps these catalogues become part of a digital project where content is cross-referenced at large, making them a next-level reference with access and discoverability.

What do you consider to be the Holy Grail of your collection?

Considering the economical improv of my collections, together with fun and knowledge from unexpected places, I think I am more interested in a Rosetta Stone than a holy relic. Searching for keys is a major reason I turned to catalogues and a reason I now work with other archives. For example, researching Dennison’s publications — with help from the Dennison archivist at the Framingham History Center — revealed that a cryptic numerical marking on decades of that company’s publications offers a meaningful glimpse into their printing history, which in turn ties to products within.

I will say, for research, that manufacturer catalogues are often a boon to library data, while some items are simply more fun to peruse. Dennison, again, is great for all the artwork usually filling their promotional printing. I also thrill at finds considered non-canonical by established collectors, particularly international. I have vintage catalogues from Canada and many from Germany. There is a surprising amount of crossover market items — including my favourite, Halloween.

What advice would you give to someone interested in starting a similar collection?

I guess my advice would be to leverage your resources. To this day, collecting for me is more meaningful when cobbled together affordably, whereas waxing about rarity, worth, and other elements seems to disfavour my own life experience; and besides, the things inside these catalogues were worth but pennies at the time — and some are still!

I would recommend first utilizing free online resources and search tools. Even though novelty catalogues aren’t always accessioned by large institutions, there may be a local society, for example, that holds discoverable copies. I ran across a catalogue by Western Novelty Co. without knowledge of its content. Searching further, I discovered that the nearby History Colorado Center had that company’s catalogues (1920s to 1990s). I managed a visit, and even though they are not the content I personally sought, they are still a great resource for others seeking info on other types of novelties! You just have to put in the time searching, and sometimes the payoffs are amazing.

As for purchases, I always say start small and inexpensive. I don’t start spending big for two reasons. First, spending a small amount on an item lets you learn whether it is really of personal interest before spending more money. Second — and this relates more closely to publications — print numbers were probably large enough that you can start small and spend more later when filling a needful gap. For example, through my research into Dennison mentioned earlier, I learned that many booklets were printed in numbers from 25,000 to 190,000 in a single year; that is good information when buying a collectible catalogue as a source.

Discover Aaron Wiley’s Halloween Retrospect archive library.

Drop us a line to let us know about your collection of vintage toys and/or games. We just may feature your collection!