As the iconic toy company returns, we reflect on the impact it had on a generation.

At the annual Mego Meet convention in June 2018, a robust looking Marty Abrams announced the return of his family’s brand, Mego, to Target stores across the country. This news was met with excitement from attendees, who had hoped for this day. If you grew up in the “post-Mego” world, it might seem puzzling why, in a world of action figures with their own animated series and where almost every movie is preceded by a toy line, people are so excited. Many people don’t realize Mego pioneered the action figure industry.

A small family business that sold inexpensive impulse toys, Mego would shift greatly when the second generation arrived, mainly in the form of founder D David Abram’s son Marty. Marty Abrams had ambitions of being a Madison Avenue advertising executive but instead brought his creative skills to the family business and changed the toy world in the process, through the magic of licensing. Pre-Mego, licensing was considered risky, occasionally top-rated television shows like Bonanza would receive action figures, but even recognizable characters such as Batman were considered “fads,” and movies were too much of a gamble. Action figures relied heavily on “house brands” such as G.I. Joe and Big Jim, whose popularity was mainly based on a saturation of television commercials.

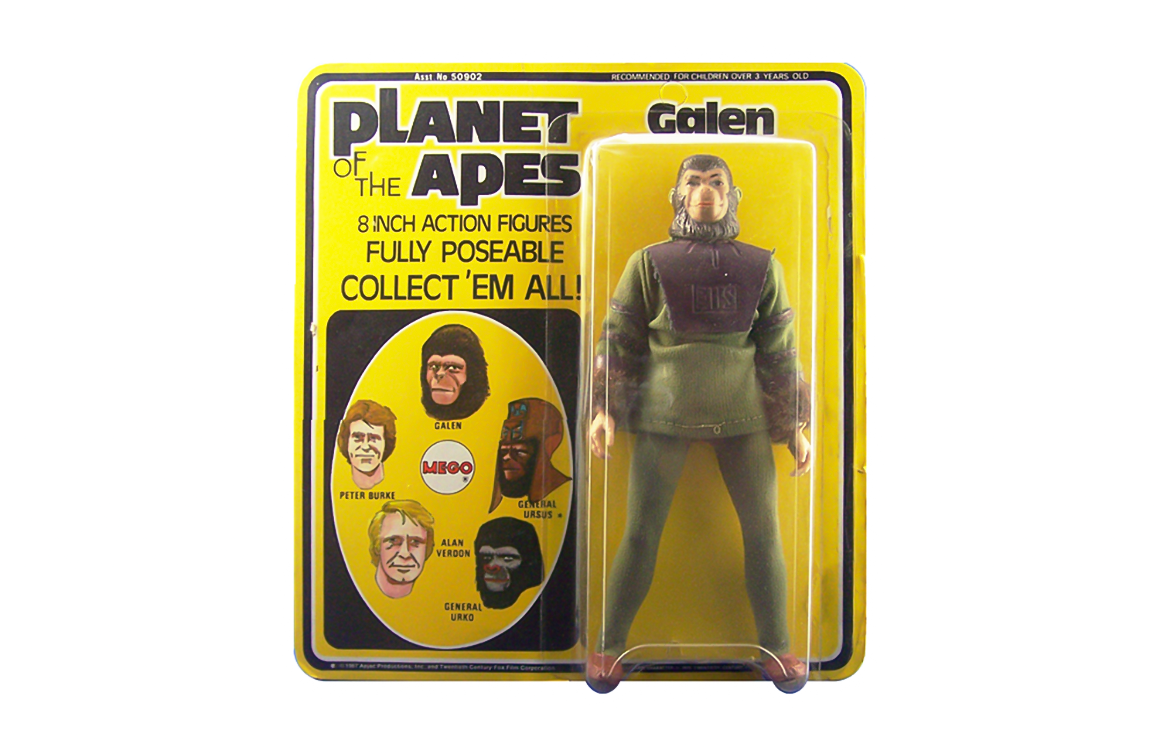

Mego had followed suit, but the ambitious ad campaign for their “Action Jackson” line of adventure dolls had suffered the wrath of stringent 1970s standards for children’s advertising, the company had an expensive problem in the form of unsold action figures. The solution to this problem was the turning point, licensing the Superhero characters of DC Comics and Marvel Comics turning unused Action Jackson bodies into crime fighters. The superhero gambit, while considered risky at the time, was an instant hit and other television and movie favorites followed every year including Planet of the Apes, Star Trek, and even Starsky and Hutch. Mego had created an inclusive universe of action figures, all properties in the same scale and it offered worlds of adventure for the average child.

The company also smartly hired young people, fresh out of art school, who had a passion for Mego and exploded their creativity onto everything they touched. The greatest indicator of that success at the time would how many copied the Mego style, even G.I. Joe, would shrink down four inches and become “Super Joe” by the end of the decade. The ride would continue in the early ‘80s, and while every license wasn’t a hit, Mego was still riding high figures based on television hits like “The Dukes of Hazzard” and “CHiPs.”

Due to legal issues and over-investment in electronic games, Mego would close its doors in 1983. To a generation of kids, a lot of magic left the toy aisle. Mego fans have kept the torch burning with websites such as MegoMuseum.com and an annual convention called “MegoMeet” brings fans from all over the world.

The joy at seeing that familiar Mego logo in retail again is making a lot of ‘70s kids (myself included) very happy indeed.

![]()

Brian Heiler is a life-long Mego fan, curator at The Mego Museum, webmaster at Plaidstallions, and author of Rack Toys: Cheap, Crazed Playthings.

Note: If you buy something using the eBay link in this story, we may earn a small commission. Thank you for supporting independent toy journalism!