What inspired you to write Radical Play?

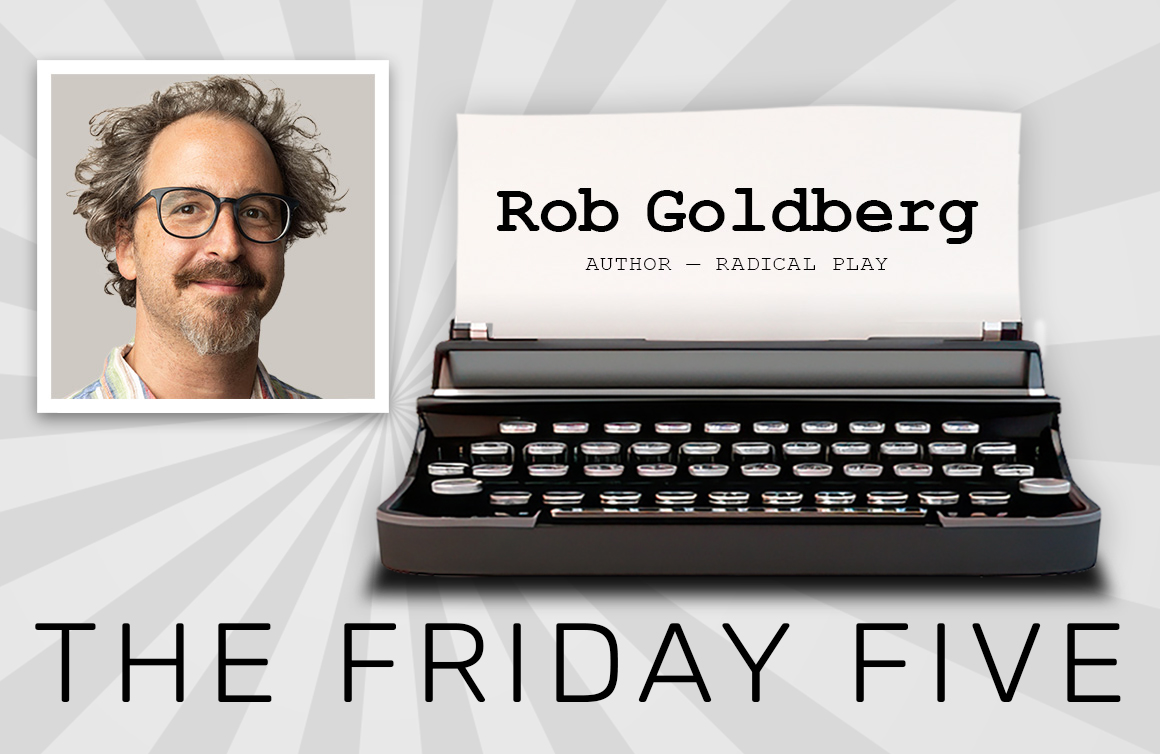

Radical Play was born out of a desire to tell American toy stories that I felt were missing from the narrative of American playthings. For instance, the story of the 1950s and the commercial revolutions of that time have been told often and well. The 1980s, when I came of age in Toyland, has also gotten a lot of attention from scholars and collectors. Yet so much happened in the U.S. between the birth of Barbie and birth of the He-Man.

As a historian who studied the protests and upheaval that convulsed the nation during the 1960s and 70s, from the Vietnam War to civil rights to the women’s movement, I had an inkling that those social changes must have had a measurable impact on toys. I could never have imagined how true that turned out to be; every one of those movements took up toys as a political issue.

How did you go about researching and gathering information for the book? What surprising facts or findings did you uncover during your research?

As someone who loved toys as a kid (I still have my Darth Vadar carrying case), doing research for a book on toys never felt like work. It was a toy fantasy come true, I got to become a kind of toy detective.

What I realized soon after I started the research was that almost no archival or museum collections have toys. One notable exception is the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York, where I spent two weeks early on in my research. I also took a road trip to the now-closed Marx Toy Museum with a huge scanner in the trunk of my car – this was before the IPhone – so that I could scan the incredible catalog collection of the museum’s owner, Francis Turner. I also found sources in unexpected places closer to home. I was living in Philadelphia when I began the project, and it turned out that the Philadelphia Free Library is one of only two libraries that have bound copies of all the major toy trade publications. I got to read the full-color originals. The other library is the New York Public Library, where my family lives, so I spent weeks and weeks there, flipping through Playthings and the hard-to-find Toy & Hobby World.

I also got to spend hours on eBay, bidding on toys that I needed to analyze up close, including the packaging, while trying to stick to my research budget. But perhaps the highlight was tracking down some of the incredible people I’d been reading about in the pages of the trade press or newspaper articles about the annual demonstrations outside the Toy Fair — toymakers and activists alike. Everyone I interviewed was excited to talk about that era, and I am honored to have the chance to share their stories.

You have an entire chapter devoted to Shindana Toys. How did the company address social issues and promote positive messaging through its toy designs and marketing strategies?

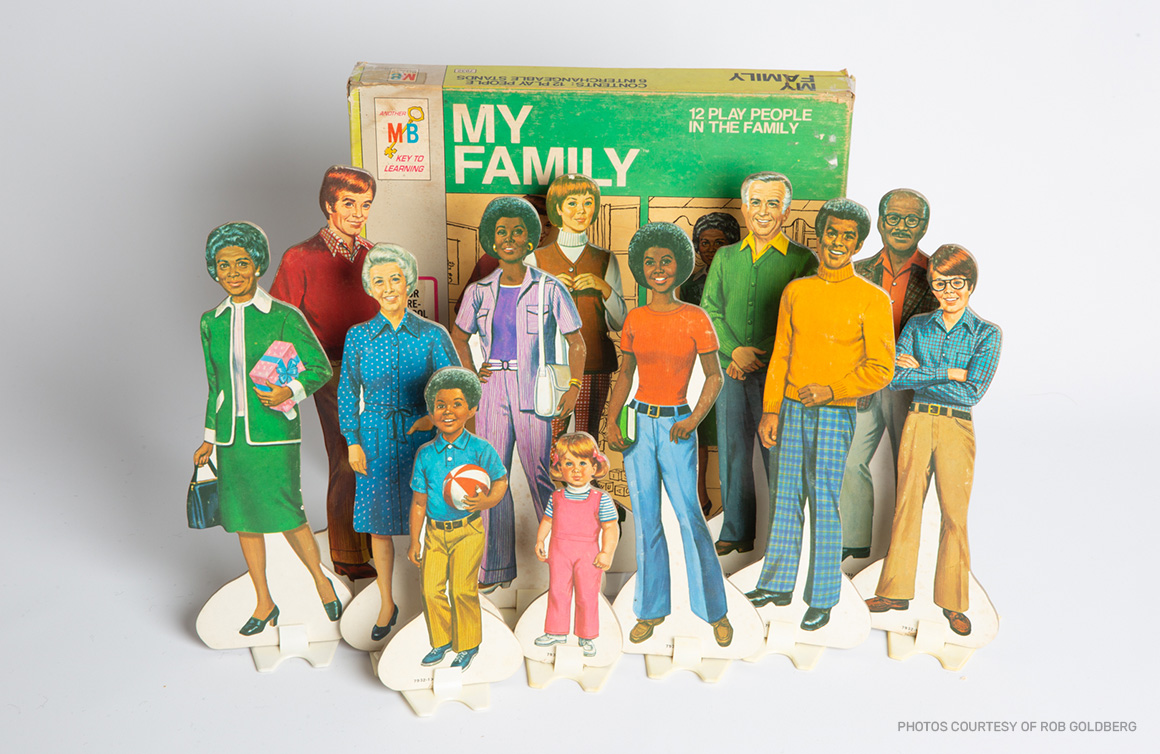

Shindana Toys was a trailblazer in every facet of toymaking, from research and development to production and marketing. The struggle for Black equality and dignity informed and animated each toy they produced.

The company’s founders, Lou Smith and Robert Hall, were both civil rights leaders of the time. Hall had been involved in local direct-action campaigns for equal housing and education for years before meeting up with Smith, who had been involved with the Congress of Racial Equality since the early 1960s, including a stint with the Mississippi Freedom Summer project. They brought these political commitments to Shindana’s representations of Black culture in ways that no toy business before or since had ever done.

To begin the process of designing a head mold for the company’s first doll, 1968’s Baby Nancy, the company invited local high school students in South Central Los Angeles to submit their drawings. For the Black leaders of Shindana, it was essential that the company’s doll aesthetic not only reflected a dignified image of Black children that could counter the industry’s long history of demeaning stereotypes, but also came from the community itself.

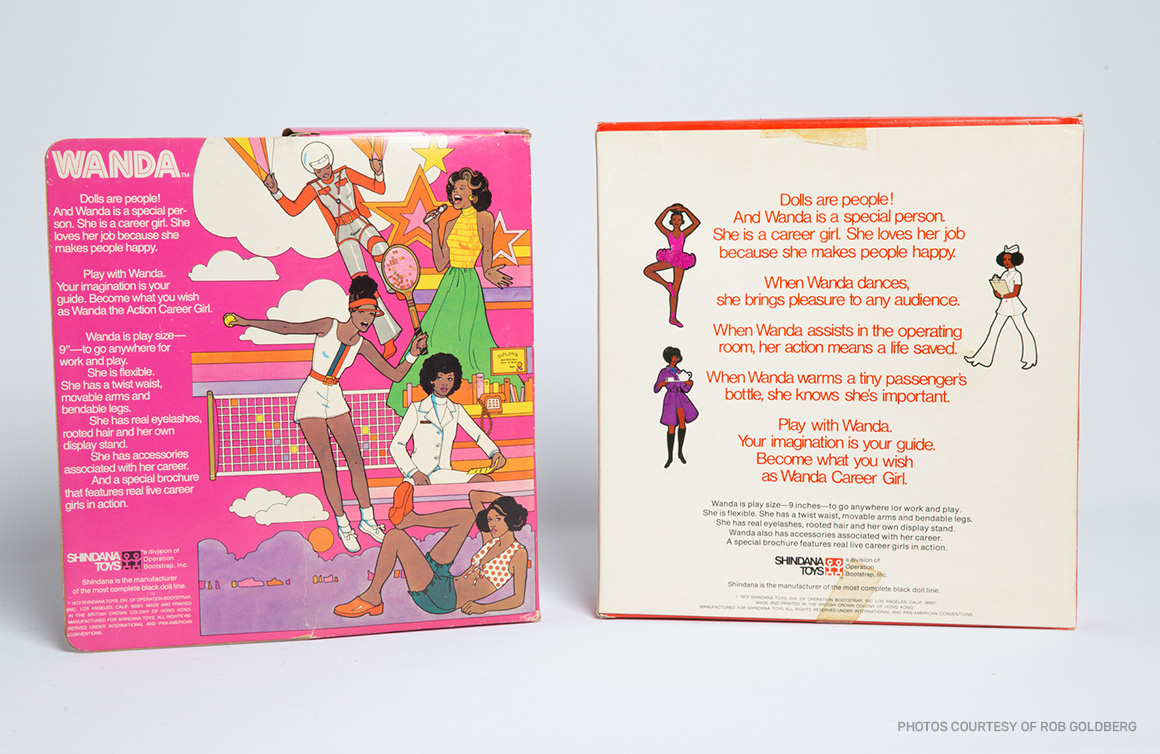

Other dolls in the Shindana line also reflected the company’s desire to represent and celebrate Black identity and experience. Another example is the Wanda Career Doll, introduced in 1972, and which came with a tiny career-oriented pamphlet in the box. Inside the pamphlet were photos of real Black women in various professions, and each photo was accompanied by a first-person narrative explaining how the person came to her career. A volunteer for Shindana named Jeep Ransaw ran the Wanda Career Club, answering letters that little girls wrote to “Wanda” and giving them advice for how to pursue their own career aspirations. Importantly, this was a time when Mattel’s Barbie had been stripped of career aspirations with the introduction of the Malibu theme in 1971.

Shindana was not a traditional for-profit business, but the subsidiary of Operation Bootstrap, Inc., a non-profit community development and job training organization founded in 1965 after the Watts Uprising. Bootstrap’s motto was “Learn, Baby, Learn,” and Shindana made sure to infuse all its dolls with that vision of education and uplift.

Radical Play highlights two ground-breaking dolls from the 1970s: Kenner’s Dusty and Ideal’s Derry Daring. What influence did these toy lines have on today’s objects of play?

I’m not sure Dusty and Derry did much to influence the toy business then or since, but they stand out as remarkable material evidence of the lengths that toy manufacturers went to in the 1970s in hopes of connecting to the growing number of feminist mothers who were buying their toys.

Dusty’s myriad athletic interests reflected the influence of 1972’s Title IX on American girlhood. Built with a unique spring-action mechanism so that she could swing a tennis racket or a baseball bat, Dusty’s sporty reimagining of the Barbie formula led Kenner to coin a new category – the “fashion-action doll.”

Meanwhile, Derry Daring, with her Gumby-like composition and daredevil motorcycle, seemed to embody Helen Reddy’s 1972 pop anthem “I Am Woman”, where she sings “You can bend but never break me/’cause it only seems to make me/more determined to achieve my final goal.” Daring never achieved Ideal’s goal of knocking Barbie off the top of the fashion-doll bestseller list, nor did she sell in numbers anything like Reddy’s single. The next time the industry’s major players attempted to appeal to feminist sensibilities with a different kind of fashion doll was probably when, more than a decade later, Hasbro introduced the Jem and the Holograms line.

You were a guest expert for History Channel’s The Toys That Built America. Tell us about the experience.

It was a blast. They put me on an Amtrak from Philly to New York, and then had a car service pick me up at the train station to take me to the studio in Queens. If that wasn’t enough, I got to sit for two hours with a super kind producer with an encyclopedic knowledge of the industry and talk toys, one topic after the next: Marvin Glass, Star Wars, Sega, Teddy Ruxpin, Photon.

In the end, the only episode I made the cut for is the one about the Cabbage Patch Kids and Garbage Pail Kids. I have two or three brief moments, but I get to be the one who recounts the moment that Roger Schlaifer came up with the name. And for me, having grown up with several Cabbage Patch Kids and shoeboxes full of delightfully gross GPK cards, I was over the moon.

Bonus Question: Many of the photographs in the book feature toys and ephemera from your personal collection. Tell us more about it and how long you have been collecting.

I’ve been a collector in two stages. First, as a kid born in 1978, I grew up on Star Wars, GI Joe, and M.A.S.K. A few prize possessions from that era are my Sato doll from Karate Kid II, my Yoda figure, and perhaps my personal favorite, the Lone Ranger figure made by Gabriel. My father used to tell me about the Lone Ranger radio shows from when he was a kid in the 1940s, and so that figure also carried a different kind of nostalgia.

I stopped collecting toys until I began the book, and realized that I needed direct access to the actual toys I was writing about, much like an archeologist writing about an ancient civilization needs to be able to hold the artifacts. Even the Strong Museum didn’t have all the toys I was writing about. eBay did, for a price, and I paid it. I’ve added dozens of dolls to my collection since, including every toy on the book’s cover.

Visit Radical Play the Book to delve deeper into Rob’s work and purchase your own copy!