How would you describe manga to folks who are new to the genre?

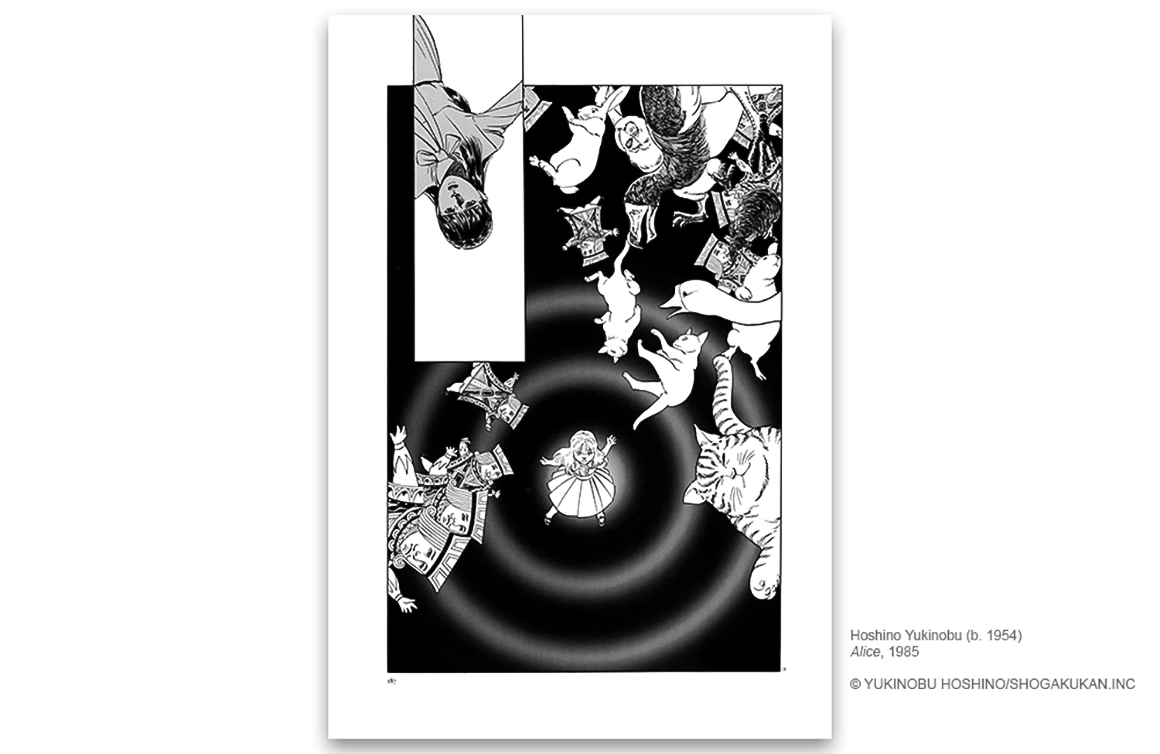

Manga is a visual form of narrative storytelling that employs the power of line drawing to literally draw the reader into the story. Manga’s roots are international, but the form as we know it today developed in Japan in the late 19th through to the 20th centuries and has recently achieved global reach. The manga phenomenon is expanding to animation (known as anime in Japan), art, fashion, street art, graffiti, and newly developed forms including digital multimedia and gaming. It is a multi-billion-pound industry super-fueled by its readers and viewers. It is immensely popular with people of all ages in Japan and, increasingly, all over the world.

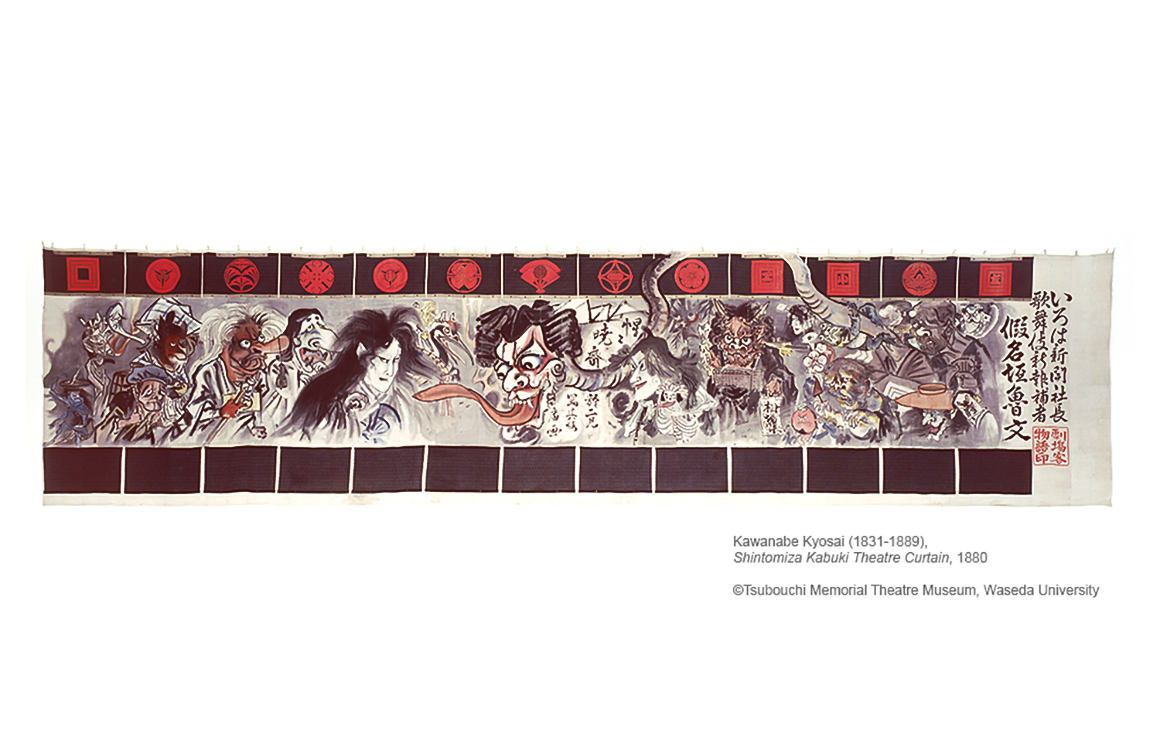

Manga as we know it today has roots that reach across continents and centuries. The prehistory of the form derives in part from Japanese traditional artistic and literary practices. Sequential images and texts were a crucial part of Japan’s artistic heritage from the 1100s onwards, first seen in painted hand-scrolls such as Frolicking Animals (Chôjû giga emaki) in Kôzanji temple and now in the Kyoto and Tokyo National Museums.

In the 1600s, inexpensive comical picture books roughly printed in a format called toba-e started to gain popularity. By the late 1700s, comic illustrated novels known as kibyôshi were printed in large numbers for the newly enriched and literate townspeople. Similar social climates in the later 18th century – coupled with new, cheaper printing technologies and rising literacy rates – helped printed social satire to thrive in Japan and Europe.

In the 1860s, the first newspapers printed in Japan were created in Yokohama – one was Japan Punch by Charles Wirgman (from 1862-1887). Kitazawa Rakuten (Kitazawa Yasuji, 1876-1955) created the first serial comic with recognisable characters in Japan, and is credited as being one of the first truly modern manga artists. Modern manga was born from this new international milieu of serial cartoon strips. Okamoto Ippei (1886-1948) worked for Asahi Shimbun and was the founder of the Nippon mangakai, Japan’s first society of manga artists. In the 1920s, he arranged for syndication of US cartoons in Japan, such as George McManus’ Bringing up Father and Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff. Ippei also created a school to encourage manga artists to work in individual styles based on four-panel manga (called yonkoma).

A breakaway manga success in the so-called red book (akahon) format called Shin Takarakuji (New Treasure Island). It was drawn in 1947 by 19-year-old Tezuka Osamu and written by Sakai Shinshima, and rapidly sold a sensational 400,000 copies. Modern manga came of age with this iconic work that was influenced by Disney, western films, and earlier Japanese manga, as the scholar Ryan Holmberg has shown in his work on Tezuka Osamu.

Why is manga important in Japanese culture?

Let me answer by giving examples. Manga is fast becoming a visual language employed almost everywhere in Japan, both high and low. Even Kyoto, the bastion of Japanese traditional culture, has commissioned a series of manga posters illustrating local beauty spots and characters to encourage people to explore the city. Manga has also become part of the establishment in Japan. The Japanese Foreign Office recently started an information and recruitment drive using the famous manga artist, Saito Takao, and his James Bond-styled hard-action man, Duke Togo, the infamous Golgo 13. Upon entering the Japanese Embassy in London, his bold black line-drawn figure glares at you on a bright, hard-to-miss yellow background. He is showing us that manga is here to stay and that we ignore it at our peril.

The Japanese government has employed manga for the last decade in advertising Japan to foreigners through images of, for example, how to ride a bullet train and eat sushi. Underground lines throughout Japan have taken to introducing a series of seasonal etiquette posters warning visitors of the dangers of using your smartphone while walking on the platforms or the crime of up-skirting. Japan Railways has long used manga and anime not just in advertising but also in participatory games, such as issuing passport-style books and having fans stamp a famous manga and anime figure from Dragon Ball or Naruto at specific stations, with the aim being to collect all the stamps in the books.

Japan has a strong visual culture and manga works well with the country that inspired emojis (emo= emotions, ji= characters in Japanese). Kurita Shigetaka created the emoji system in 1999 for the Japan telecommunications network Docomo.

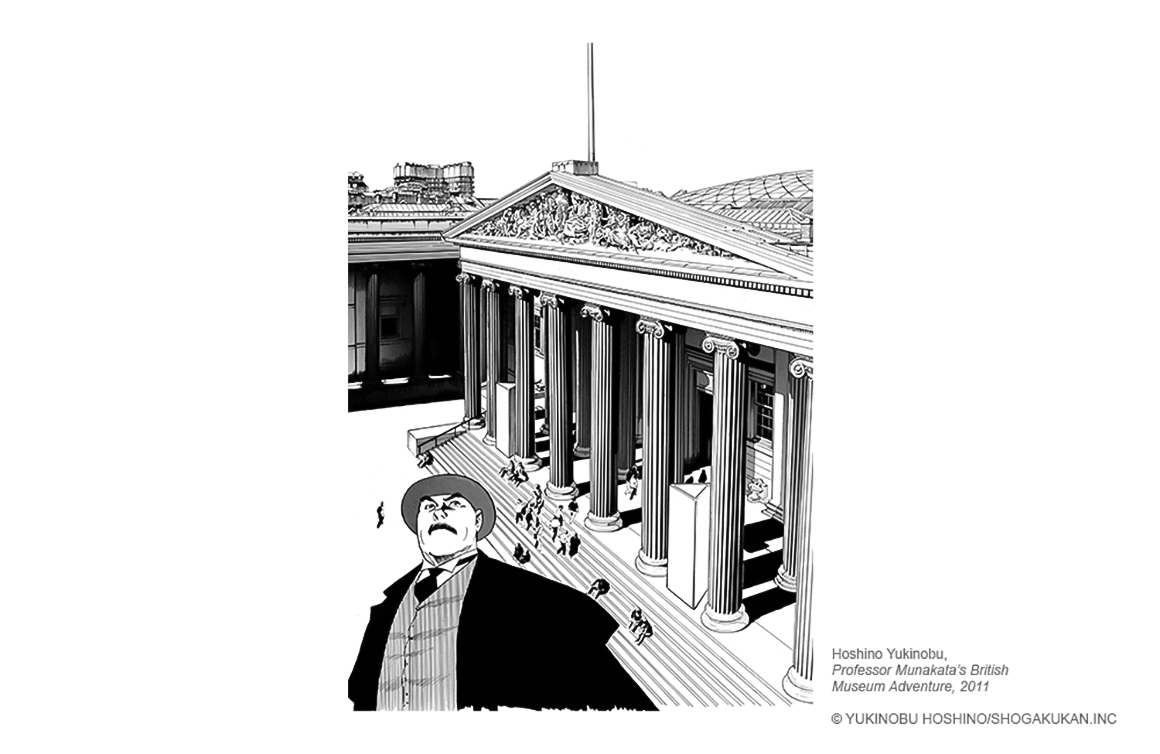

Tell us about the upcoming exhibit at the British Museum, The Citi exhibition Manga マンガ.

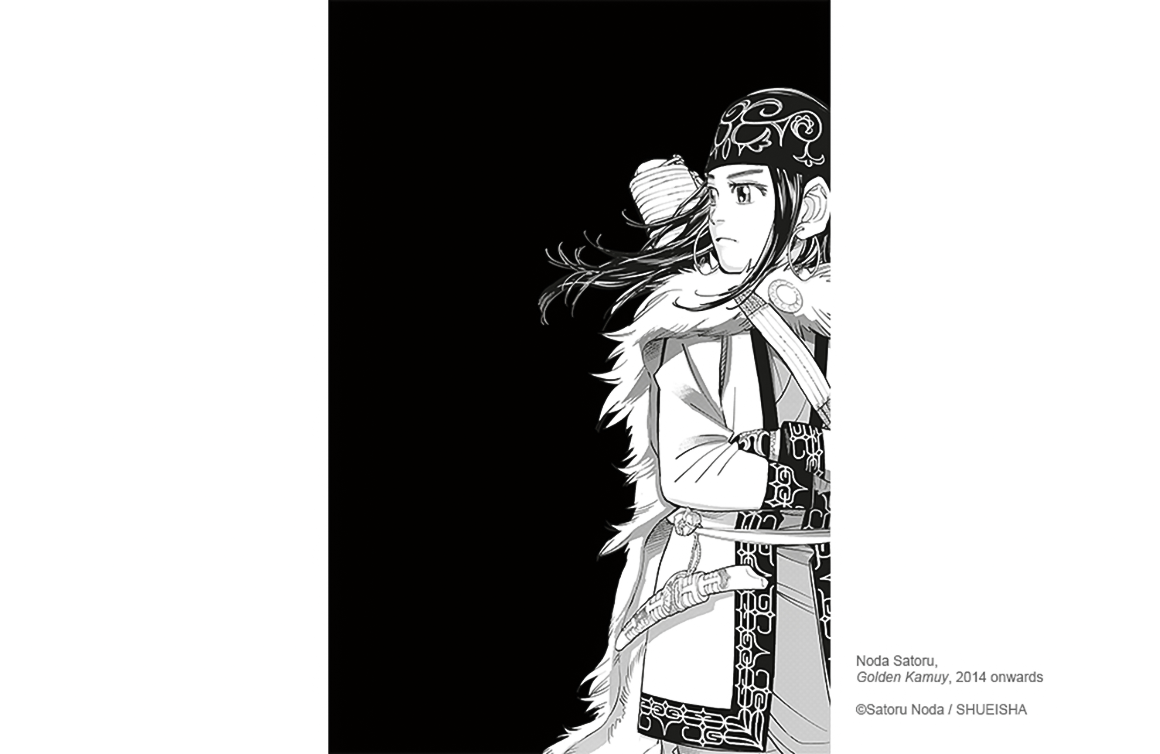

This exhibition marks an exciting new departure for the British Museum. Held in the premier space, the Sainsbury Exhibition Gallery, about 50 manga artists, 80 titles, and (depending on how you count), 185 works from historical art to digital experiments are showcased. It brings together the best examples from the past to the present and points to the future of this exciting and accessible medium. There will be analogue and digital elements. There is some audience participation and we have created a wonderful ending. The exhibition was developed with advice from a number of Japanese manga artists, editors, publishers, curators, and museums with some bespoke work, original drawings, and more.

Please come and see it for yourself!

How has manga influenced North American pop culture?

Generally speaking, it is important to remember that, in our image-driven, Instagram-influenced world, manga is a wonderfully accessible art form all over the world. It feeds an international audience that is hungry not just for pictures but also for stories. Many manga are now translated into other languages, and mobile technologies with translation apps make the once-inaccessible elements of Japanese script downloadable and available on your screen.

What do you hope visitors take away from their time at the exhibit?

Visitors to this exhibition will gain a new and readily deployable skill: they will become fluent in manga. Manga is fast becoming an international language employed from Tokyo to London in advertising, in various printed art forms and on mobile devices, billboards, and graffiti’ed on walls and clothing.

With hundreds of genres, from sports to love, and from horror to sexual identity, there is a manga for everyone. We want everyone to find their own manga and identify their manga circle or genre.

We want visitors to have fun, to be swept away by what they see, to feel provoked and stimulated by the content. We want people to feel a part of this sweeping form of storytelling, and to understand it slightly differently after emerging from the exhibition. Mostly, we hope that people will understand that manga is now becoming a global phenomenon and they have had a privileged view of it, from the inside out.

The Citi exhibition Manga マンガ runs May 23, 2019 through August 26, 2019. Learn more about the exhibit on britishmuseum.org.