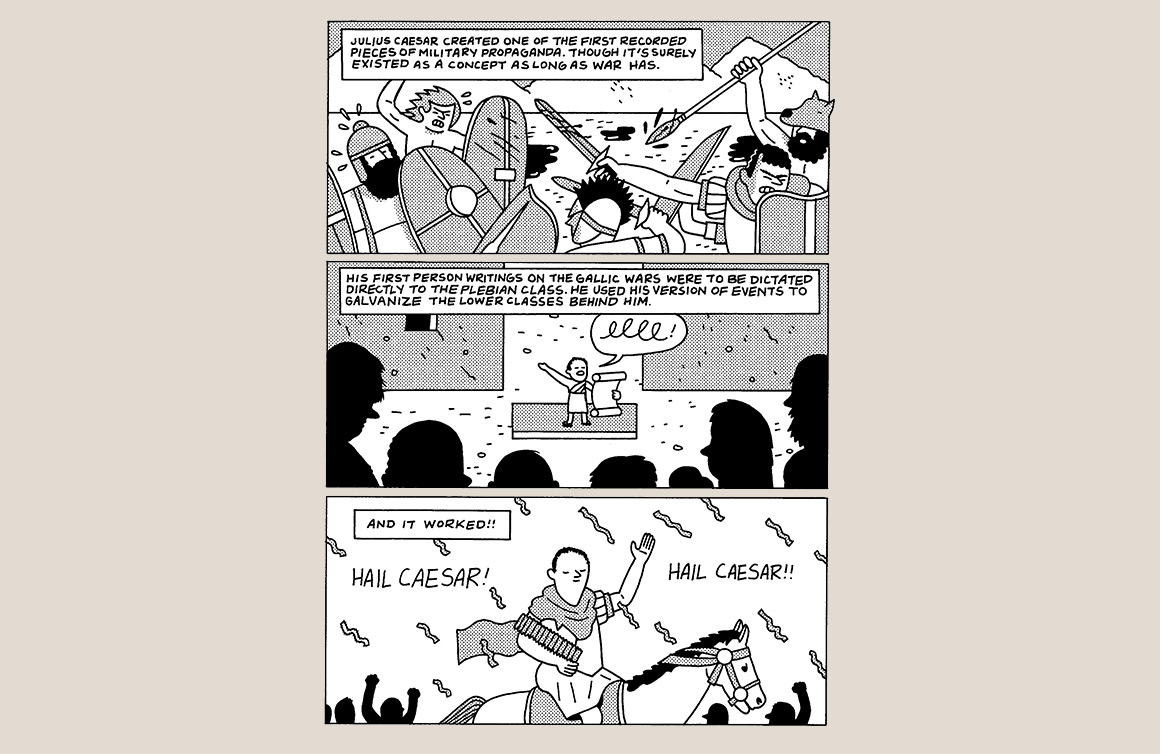

The first chapter of The He-Man Effect is largely devoted to the origins of propaganda and how it seeped from military and political use into toy marketing. Are our childhood memories of play just brand constructs?

I think more and more, yes. But, I don’t think that’s the point of them or that they have to be that way.

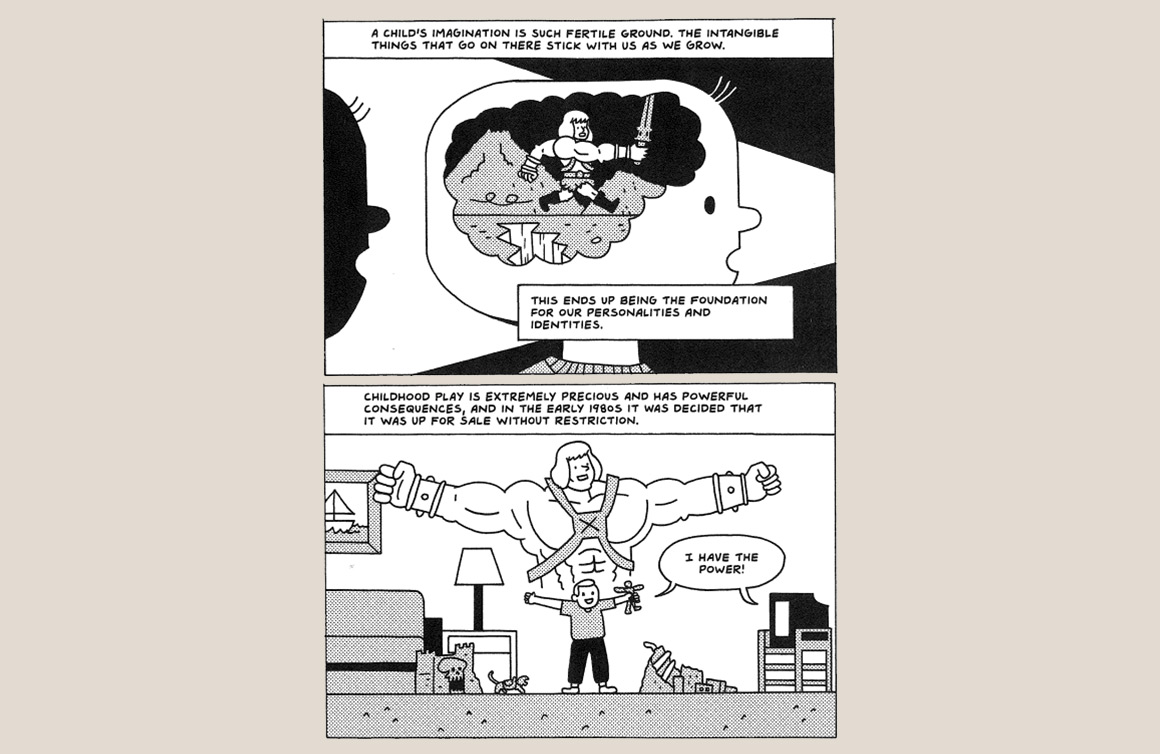

Thinking back on my childhood — 35 years ago or more — my memories often involve a He-Man or Transformer. Cherished memories with my family members are me begging to go to the toy store with them and things like that.

You don’t really have control over the things that you feel nostalgic about. It can be something totally random. There can be things that you did a lot that you don’t feel nostalgic for. For myself, I played little league when I was a kid and I don’t really feel nostalgic about wanting to have my kids do little league stuff.

Pop music is also like that. A friend of mine pointed out that there are songs that you can feel nostalgic for. He’s a musician. Intellectually he knows when a song is not really that good. We were talking about the song catalog of Billy Joel and he was saying that it’s not something that he would — now as an adult musician — listen to. But, he actually feels a little embarrassed about the fact that he’s driving around singing Billy Joel songs when they come on. It’s a guilty pleasure thing. You don’t really have control over these things. Sometimes you just like what was around when you were a certain age. With pop music especially, we were inundated with the hits. They were just always there, so there are emotional memories that get tied up with the music that you’re listening to at any given moment.

In a similar way, cartoons get tied up with our emotions. I also talk a lot about the ways in which food gets tied up in your emotions — the concept of comfort food. That’s a nostalgic feeling. My sister and I recently started talking a lot about the concept of comfort TV and comfort movies. Again, oftentimes your comfort movie isn’t Citizen Kane. The greatest movie of all time isn’t necessarily a comfort movie in the same way that something like Beetlejuice is for me. It’s the stuff I watched a lot because it was one of the only VHS tapes we had at my grandma’s house.

You observe that nostalgia offers comfort and safety but risks becoming toxic. Can you explain that a little more?

One of the things I often think about is being at my grandma’s house. We were there a lot — every day after school and all summer.

When I think about something like reading a pro-wrestling magazine I got from the grocery store, that would be something I’d be doing at grandma’s house because I was bored or whatever. It’s the same with watching TV there. A lot of these things get tied up in that time and it’s such a safe and wonderful memory to the point where I wish I could just be back at my grandma’s house. I remember the air conditioning was really cold and she was always cooking something. But in a more realistic way, I also remember being really bored and wishing I wasn’t there. I wanted to be outside and would only go inside if I couldn’t find a friend to go play with or something else that was more fun. It was actually kind of boring at grandma’s but in my mind, it’s wonderful. I would want to go back and just be bored there.

Your memory tends to recall the really wonderful things that happened to you like your siblings being born and the really bad things that happened, the trauma. There’s all this stuff in the middle and the little annoyances get washed over. It gets looked at as this gleaming, shiny thing. You hear phrases all the time such as ‘they don’t make things like they used to’ or ‘back in my day it wasn’t like this’. Nostalgia is a really powerful emotion — it’s up there with love, laughter, and things like that. It can cause you to think that the things that weren’t so great, were great. In the example about Billy Joel’s, it’s a guilty pleasure. But if you take this into the realm of politics, you have people who think we should make things like they were in that back in the 1950s. There’s a big movement of people that want to turn the clock back when in actuality, previous times weren’t as good as the people who want to go back to them remember.

Either way, it’s a really strong feeling which can be harnessed to motivated people.

The phrase, “Make America Great Again” was a Reagan slogan that was based on nostalgia. I talk a lot about that in The He-Man Effect — Ronald Reagan’s use of nostalgia and how powerful it was. He used the cowboy motif — something that a lot of the adults who would have been voting for Reagan had a lot of nostalgia for at the time. That’s my dad’s generation. There was a lot of nostalgia for cowboys and cowboy movies. That generation was inundated with that in the prime of childhood in the late 1950s and ’60s. It was all cowboys. That gets embedded and becomes useful.

When I was trying to come up with how to do this book, or why to do the book, the first thing was determining the story. I think that what makes it into a story is pointing out that all of this stuff is due to Reagan’s deregulation of children’s media. So now, 40 years later, we are seeing the consequences of what deregulation did to a generation of children and what it might continue to do for generations to come. Reagan was deregulating everything, not just children’s media but other parts of the media, too. This was the end of the Fairness Doctrine, where we see the birth of the Rush Limbaughs of the world and we see media become more partisan to where it’s “left media” or “right media”.

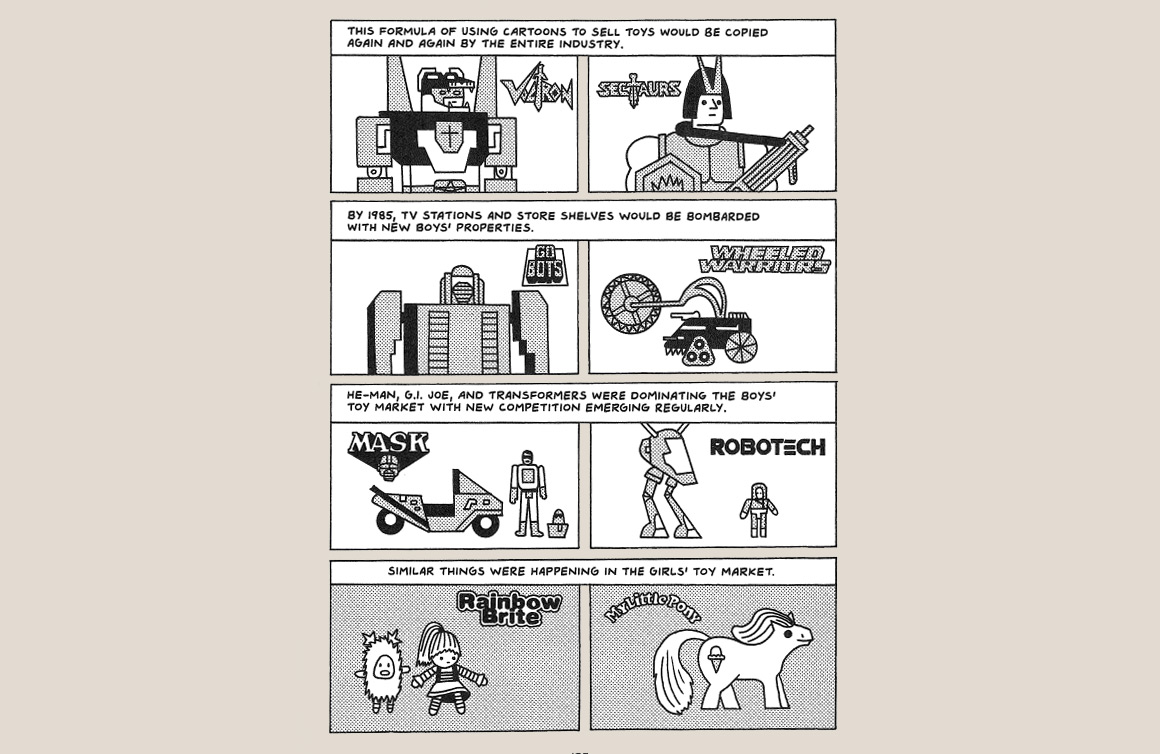

This all happened under Reagan. And He-Man, this kind of ridiculous character, ends up being one of the first big properties to take advantage of the deregulation of children’s media where they could make a television show that was essentially a commercial for a toy. They took advantage of it right away. They knew it was coming, it had been coming for a long time. Lobbying for this deregulation started in the late 1970s. We see He-Man show up as a combination of every popular thing mixed together — body building, swords and sorcery, aliens, and sci-fi lasers. There’s a constant introduction of new characters and new toys. One of my first earliest memories is of being a kid of about three or four years old playing at the playground and my mom saying, “We gotta go, we’re gonna miss He-Man” and me realizing that there was a possibility that I would miss He-Man and kind of freaking out and being like, “Alright, let’s go!”

A common theme in your books is social impact. What makes that topic appealing to you as a writer and as an illustrator?

I think I have a natural predilection towards justice, kind of like where I’m constantly pointing out that things are not fair and they’re fixed. I don’t know, it’s like a weird life obsession.

Sometimes I think my books are an opportunity to go back and fix something or fix the record or maybe point out new ways to think about something that we have forgotten. I don’t know. I mean, you’re right, totally. It’s a natural inclination, more or less.

I have a weekly comic strip about the cannabis industry. It’s all about pointing out the corruption there. I can’t help it; I have OCD and I can become obsessive about things. This is an outgrowth of that, I think.

You’ve published much of your work with First Second. What makes them a great publishing partner for your books?

If my books have any educational elements in them and can be used in the classroom or are good for students, First Second is really good at getting those in front of teachers and students. In the case of The He-Man Effect, it hasn’t been out for very long but there are already professors who have been assigning it.

They also distribute the book across the country and across the world, which is something that you can’t really do as an individual. I did a book tour and they helped with travel and things like that.

But really, it’s all about just being able to get the book out in front of as many people as possible. I self-published a lot when I was getting started. It is very difficult to distribute books into the world. As an individual, I think the most books we ever sold for any one book was 3,000 or something like that, and it took every effort that we could possibly make. There are so many different places and all these different distributing channels. It’s no small feat to do stuff like that.

You founded your own comics publishing house, Retrofit Comics, in 2011. What inspired you to establish your own publishing company?

I was self-publishing a lot of my own work and getting to know a lot about the printing process, which can be intimidating especially when you’re getting started. I didn’t know how to set it up, what the files should look like, how it’s supposed to print, who do you send it to, were does it go — all these things. I figured out how to do that.

I was putting out comics pretty often myself and thought that if I could put out other people’s comics that I’d have more product to put out. It was just like a natural outgrowth of self-publishing, But, I quickly got in over my head. I had a partner, Jared Smith from Big Planet Comics, who was a huge help in getting all these books out. But ultimately, after my kids were born, I realized that I didn’t have enough time to publish comics and focus on my own work at the same time. It just became too much.

What project(s) can we look forward to seeing from you next?

I’m working on a fiction book right now. I can’t really tell you too much about it. I have some science fiction work out there now, and if you’re familiar at all with that, it’s in that same vein.

I also work on a bi-weekly strip about the cannabis industry called Legalization Nation.

Visit Brian’s website to browse his books and art.