What inspired the War Games exhibit?

Inspiration came from two sources.

The first is that I noticed when walking through the museum gallery for which I’m principally responsible — it looks at the Cold War to the present — I would see groups of youth debating, in some cases heatedly, the benefits and drawbacks of various weapons systems that were in some of the arms cases in the Cold War section. I realized that the way that these kids were getting into military history, and were accessing it and contextualizing it, was through their experience with online first-person shooter games such as Call of Duty or Medal of Honor. They arrived with some external knowledge about weapons systems that they otherwise perhaps would not have.

The secondary source of inspiration was thinking about history, games, and play and how they reflect the wars that we’re engaged in or that are presently unfolding around the world. That struck me as an interesting theme because I myself, in my spare time, have spent a lot of time playing games — be it hobby, tabletop war games, or some of the more popular gaming franchises online. Compared to some of my colleagues who’ve taken extra time for additional research and have written more books, I instead had logged hundreds or thousands of hours on these various games. So not only does this reflect a personal interest of mine it also reflects the fact that this is one of the ways that people access history and reflect on war. Even if it’s not necessarily all that deep, I felt that it offered some possibility for exploration.

From there, we had a considerable amount of refinement once we got the exhibit onto the museum’s calendar back in 2019. We pondered what we could do with the idea and we did much more dedicated research, relating it to the question of what the Canadian War Museum can do. Why should the war museum take this on? Well, there are many conflicts during which militaries have professionally used war games as a way of preparing. That intersection between real-world history, the ways in which war shapes play, and also the way in which people play war games for fun all seemed to be a rich mélange to work with.

The subsequent couple of years were largely spent refining that idea, seeing what artifacts and experiences might be available that could help us to balance between that professional military preparation side and what the public is absorbing of war, through tabletop games, miniatures, or videogames. We then conducted visitor studies and did other work to get to the finished product.

Walk us through the exhibit. What will visitors experience?

We developed an exhibition with five zones, divided mainly chronologically and trying to hint at or point to areas where there are very clear intersections between the way in which games have been shaped by war and the way in which games have perhaps shaped war through their professional application.

The first area looks at war games from antiquity to the present. It’s basically a recognition of the fact that games about war or games that simulate war have a long history — the oldest artifact in the exhibition is about 2500 years old. It’s a Greek amphora depicting a war game being played between two heroes of the Trojan War. They’re on a break from the siege and they’re playing a game.

There are other games that have a long history like Go or chess that spread through different cultures. The original point of those games was to simulate Indian army maneuvers through an abstract simplification. Now they’ve become games played around the world with different rules and different pieces that reflect local cultures. These are ancient games but they’re also very current. When visitors walk into the exhibition, they’ll recognize these games and will learn about the history. Some of the oldest war games were just a simple gambling games played with dice. We have examples of Roman and Egyptian die that date back centuries. Again, these are antiquities but also very present-day, recognizable forms that speak to the fact that war games have a long history.

In the second area, we jump ahead to war games from before the First World War to the end of the Second World War. We look at the ways in which some games like chess became adapted in the 19th century into map-based, war game simulations that became very popular in Germany first, then spread to most other European countries and North America. We have a very intricate war game set that was developed in the United Kingdom — examples were found in Canada as well — which takes the opportunity to wage bloodless wars in order to prepare officers and men to think about how to wage war using the technology and materials of the time and to take full advantage of the landscape. We have a really intricate and beautiful set — it’s the first time it’s ever been displayed — that comes to us from the National Army Museum.

At the same time, miniature war games and miniature soldiers were all the rage with people in the years leading up to the First World War. We have an example from the family of H.G. Wells, who, in addition to being a science fiction author, was also the publisher of the book titled Little Wars, which is a real miniature war game ruleset. His proposal was that if we played little wars, and resolved differences that way, then maybe we wouldn’t have to fight big wars. Of course, he published this in 1913 and a year later the world was at war.

From the Second World War era, we look at a real-world example of how war games were used professionally to adapt and innovate tactics during a very scary time — specifically, during the Battle of the Atlantic when merchant ships were going from North America to London and to Russia and being targeted and picked off by German submarines. If the Germans had been able to successfully cut that supply line, the ability to to wage war against the Nazis would have been greatly impaired. As they considered the ways in which they thought about how to best the submarine — there’s technological answers, there’s training answers, there’s tactics — all of these came into play in these very simple game simulations fought through in an attic in Liverpool, called the Western Approaches Tactical Unit. We’ve reconstructed the gaming room and put in place a game table where we’ve simplified the type of game that they were playing, and we invite visitors to sit down with one of our frontline staff, who guides them through a crossing of the Atlantic and asks them to make some of the same decisions that convoy commanders would make. By the end of the trip, you have a sense of how dangerous the crossing was, how important it was to best the U-boats, and how many losses you could take just in the simple crossing, through chance, through weather, through enemy attack. Combat commanders would come in to Liverpool, in some cases bloodied from combat, and then go and attend a week-long class where they’re being challenged on how they should react when a submarine appears, how their tactic strategy should change. This had real-world benefits in teaching and introducing new anti-submarine tactics that were then employed in the waters. It didn’t win the war on its own, obviously, but it was part of the war-winning exercise.

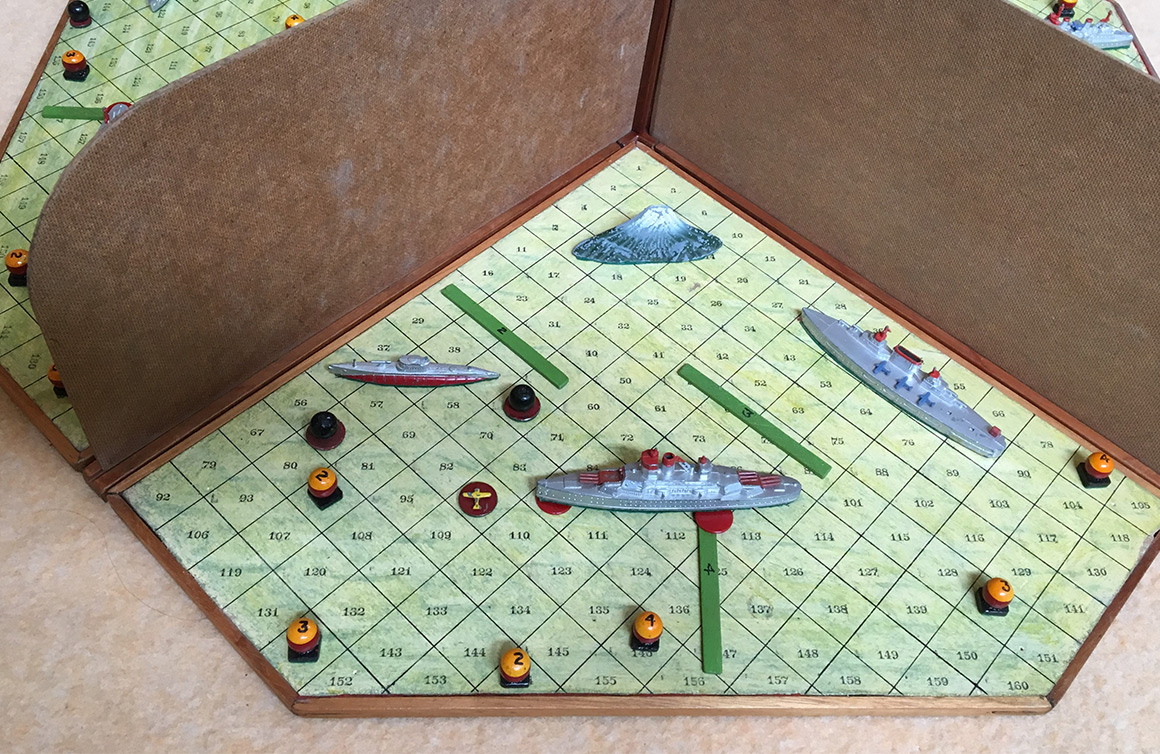

The back end of the second zone is a rich collection of examples of the ways in which the war seeped into the living rooms and parlors of Canadians and folks in Japan, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Included are rare board games and toys from the Canadian War Museum’s collection as well as examples from the collection of David Stewart-Patterson. We feature a German game where you’re playing as a U-boat captain trying to cut off the Royal Navy. Whomever this player was during the Second World War was actually noting down on the backs of the game cards which British ships were sunk and who sank them. This person was actively keeping track of the war through games. We have examples of some of the familiar games, such as Battleship and a similar four-player version called Broadside that is intricate and very interesting, loaned to us by David Stewart-Patterson. It shows the war in the living room and how people were consuming this partly as propaganda — it’s very patriotic — but you also get a sense of some of the challenges of the war, that in some cases, loved ones might have been fighting, and sometimes loved ones were sending home toys as a way of connecting with family that they were separated from.

The third area looks at games in the Cold War and the ways in which hex map games became popular in the years after the Second World War. These games had a professional application of greater importance because living in a post-atomic bomb world, war games were helpful to simulate what you couldn’t simulate in the field, which was the use of nuclear weapons. War games were used as a way of simulating and looking at tactics and even gaining diplomatic avenues. At the same time, people at home were kind of fighting the Cold War through through board games.

One of the things that changes during this period is the introduction of computers. Defense departments purchased computers in great numbers, they used them to automate their systems, and to better monitor the skies for air defense. Inevitably, the commercial applications of these computers turned to games.

Some of the first defense computers actually had some of their time hijacked to develop the first video game. We have some examples of that and how it came home through the Magnavox Odyssey and the Atari 2600. These kinds of iconic game systems really hit their boom time in the late 1970s and early 1980s. We have a playable example of an Atari game called Missile Command, which is really a simulation of the Cold War where you’re trying to intercept nuclear missiles that are coming down on your cities with missiles of your own. There’s no way to win this game, you just keep playing and racking up a high score, but eventually the missiles are going to get through and the game is over. It does make light of the Cold War, but it speaks to that existential threat. That’s paired with a defense computer being used to monitor airspace. People were working 24/7 to watch the skies to avoid a nuclear war, and people were at home playing the game on their Ataris, essentially playing through that war as if it did become a reality.

In the fourth area, we have a an exhibition space that looks at the games in the war on terrorism — Afghanistan and Iraq — and how that shaped a lot of the games that we play today. We kind of come full circle where people are playing Call of Duty and talking about these various weapons systems. That’s where we talk about some of these games and how they became so popular, really making a change in perspective from the general’s view of the battlefield — such as you’d see in a game of chess or in some of these more popular hobby games — into the boots of a commander or soldier on the ground experiencing war from the first-person perspective. Balancing that out are some viewpoints from specialists who study video games and their impact on society to answer the question: do video games cause violence? The answer is, well, no, but some of the perspectives they’re putting forward are and some of the things that are represented in games can be harmful in ways that we perhaps haven’t thought about.

We’ve also brought in some perspectives from people who served in Afghanistan and also play games. They differentiate their own real-world experience with the war games they play as an escape — what the games get right; some of the actual visual representations of weapons — but also what they get wrong, which is pretty much everything else. It’s really quite an interesting perspective.

We then look at how these popular game systems became attractive as simulation tools for the military — taking off-the-shelf software and repurposing it as mapping and simulation tools, using games as a means to reach people as a recruiting mechanism or a public information vehicle, and also the way in which medical specialists used game technology to help people who had suffered real-world and very traumatic injuries learn to walk again through an immersive virtual reality / augmented reality experience using treadmills and prosthetics. These are interesting connections.

There was also an era of pushback about the ways in which the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were being fought and how games became a method of communicating that critical perspective. We have an art installation from a biome collective based in Scotland which looks at a drone strike on one screen from the viewpoint of a drone pilot and on the other screen of a little blob running around a village as a target on the ground. This moment of distance from the drone and visceral presence of the person targeted on the ground is a point of connection where two visitors can look over each other and say, oh my goodness, this is a shared experience but very different experiences.

The final area of the War Games exhibition looks at Gaming Global Insecurity, how games have been developed by serious gamers — military and civilian — to look at global problems such as climate change and humanitarian disasters. Also, it looks at how games like this have been used to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and more recently guiding some responses to the invasion of Ukraine since 2022. In this area we conclude with a section that looks at how game designers have made meaning of war through games, either by looking back on historical conflicts or by developing games that try to build empathy with those caught up in conflict.

One of the final experiences in the exhibition is a simple interactive based on an existing mobile game, Bury Me, My Love, which follows a Syrian woman as she escapes the civil war, guided on her journey through text messages from her husband back home. We replicate two of the choices she is faced with during her journey.

In what ways have the games we play at home been shaped by real-life military conflicts?

As I mentioned earlier, a lot of the games that we play about war hold up a mirror to the world in which we live, so games during the World Wars, Cold War, or during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq took on some of the character of those wars. We see tabletop and video games evoking the conflicts, the combatants, the technology, and terrain that is being fought within the real world. These are games, not war; but nonetheless, war seeped into games just as it did into film, literature, radio, and other media.

Some of the games we play are meant to allow gamers to viscerally play through a contemporary conflict as though they were directly involved. Some are propaganda or meant to educate about the war industry and such things. Others are published with the intent of offering critical perspectives about war and its costs. I offered the example of Missile Command for the Atari being one such game shaped by its Cold War roots. I could offer dozens more, but visitors will see that for themselves when they visit!

Gaming also plays a role in the training of military personnel. How has that approach evolved over time?

As times and technologies have changed the ways in which militaries around the world have used games, game techniques have also changed.

If we take a very ancient example, like chess, that was originally the “game of kings” meant to teach strategic thinking — it wouldn’t necessarily have found its way down to the line soldier. But as time went on, a variety of strategists took chess and similar games and tried to adapt them with larger boards with more squares, different types of game pieces, and so on — in service of trying to produce a realistic war simulation.

In 19th-century Prussia, a military officer presented what was one of the most influential games, the kriegsspiel, to the Kaiser. His son had the game adopted, with refinements, by the Prussian general staff. It was a map-based game, played to scale with blocks representing units on the map, governed by an umpire and rules meant to simulate realism. Prussian military success in the 1870s led to the game being adopted everywhere and while the game pieces and maps have changed, that system of wargaming is still very much alive. We have a Cold War example on loan from the Frontier Army Museum in the United States which uses vacuum-formed plastic boards and scale model pieces to wage “war” in Cold War Germany. The look is different but the motivation is much the same.

Others took the idea of gameplay as a way to innovate and adapt tactics in real-time during the war (as opposed to pre-war training), such as the Western Approaches Tactical Unit during the Second World War, which was about facilitating games to help convoy commanders appreciate different methods to search for and destroy enemy U-boats threatening their ships.

In more recent times, game technology and techniques such as video game engines have been repurposed to provide virtual battlefield training. It’s cheaper and safer than going out in the field, allowing for safe ways to fail and learn without the cost in blood and treasure of actual warfighting.

What do you hope people take away from the War Games exhibit?

First of all, I sincerely hope everyone enjoys their visit and learns something new. We strived to find a way to present history about a common activity that most people enjoy in a unique way.

Secondly, I want people to understand that war is not a game. Games aren’t warfare. But the interconnections between these two activities — one innocuous, the other terrible and world-shaking — produce some genuinely interesting chapters in military and popular history that I think people will find very interesting.

I hope they leave thinking more closely about the things they do for fun, its history, and how it might have been shaped by war.

The War Games exhibition runs through December 31, 2023. Visit the Canadian War Museum website for more information.