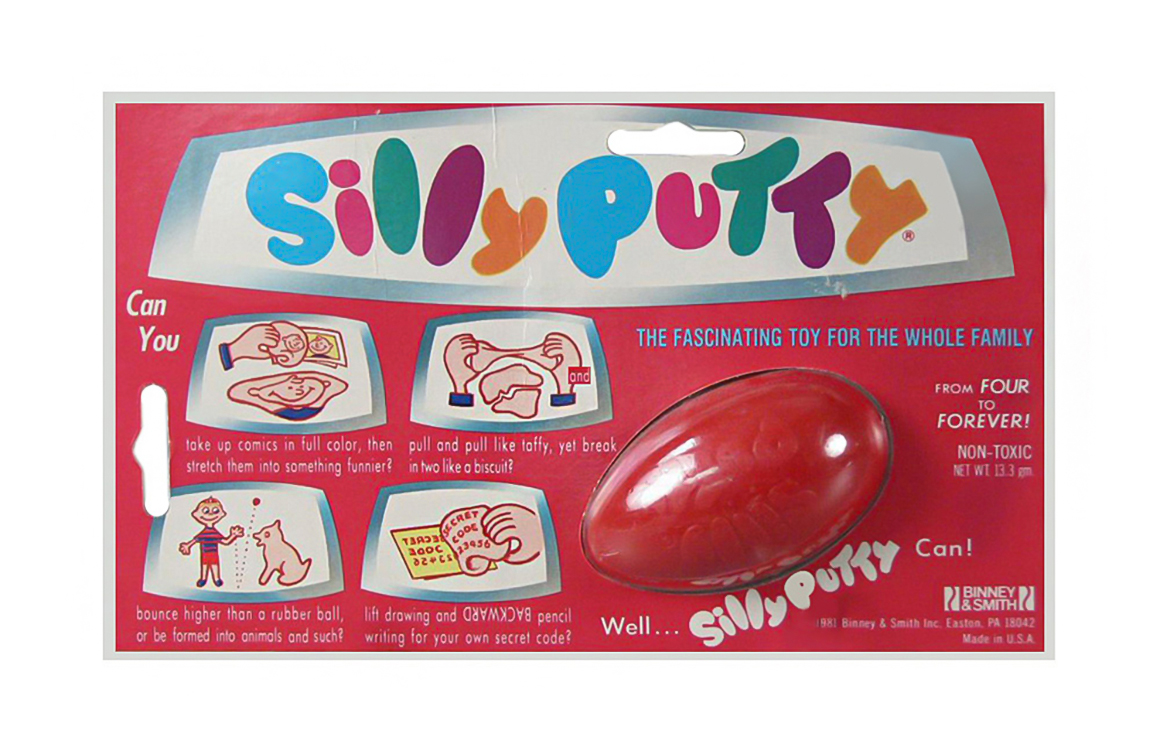

The phrase “solid liquid” is a textbook example of an oxymoron. It is also an apt description of Silly Putty, the ubiquitous “blob of goop” that has, for almost 65 years, provided countless hours of entertainment to millions of adults and children. Currently marketed by Crayola, the appeal of the novelty toy is easy to understand. Silly Putty bounces, molds like clay, and stretches like taffy. One of the popular uses of the toy is also my favorite: its ability to copy text and images from comic books and newspapers. Sadly, this feature no longer works with many of the newer inks being used today by the publishing industry.

Silly Putty was invented by accident, the result of a failed experiment undertaken during World War II to develop a synthetic alternative to rubber. Wartime rationing and a scarcity of the material led the War Production Board of the United States government to fund research by private corporations into synthetic rubber compounds.

TWO INVENTORS, ONE SILICONE SUBSTANCE

Patriotism, the drive for innovation, and profit potential led several notable companies in the U.S. to take a stab at creating synthetic rubber. The quest also resulted in multiple organizations and individuals claiming credit for the invention of the substance that eventually became known as Silly Putty.

The most widely accepted story (and the one endorsed by Crayola) attributes the invention of this toy to James Wright, an engineer working for General Electric in New Haven, Connecticut. During one of his failed experiments, Wright had combined boric acid and silicone oil to produce a gooey substance he referred to as “bouncing putty” in the U.S. Patent (#2,541,851) he was awarded on February 13, 1951. According to Crayola’s archives, the patent was the result of work Wright began in 1943.

Earl Warrick, an engineer at Dow Corning in Midland, Michigan, also claimed credit for Silly Putty. Not surprisingly, the backstory behind his invention (search for rubber substitute, unintended results, etc.) shares similar characteristics to James Wright’s version. The big difference between the two is that Warrick was awarded a U.S. Patent (#2,431,878) for his work on December 2, 1947, roughly three years before Wright and G.E.

Neither Wright or Warrick found a wartime use for their new silicone substance or realized any significant financial reward for their invention.

LIFE OF THE PARTY

Despite no apparent practical use for his “bouncing putty”, samples of Wright’s creation continued to make the rounds in various scientific and industrial circles. The substance also began to make cameo appearances at parties, amusing guests with its capabilities. At one such party in 1949, it caught the eye of Ruth Fallgatter, owner of The Block Shop, a toy store in G.E.’s hometown of New Haven.

Fallgatter shared her discovery with Peter Hodgson, a marketing and sales consultant, who was helping her produce a sales catalog for the holidays. The pair listed bouncing putty on a page with other adult gifts. The substance was packaged in a clear plastic case and sold for $2.00. While sales were better than expected, Fallgatter decided to discontinue sales of bouncing putty and focus on selling other toys in her store.

Hodgson remained enamored with the product’s sales potential. Despite being $12,000 in debt, he borrowed an addition $147 to buy a large quantity of the putty from General Electric. After deliberating over a variety of names for the substance, he settled on Silly Putty, a name that he felt best reflected the novelty toy’s unusual and entertaining attributes.

Hodgson employed students from Yale University to package one-ounce balls of silly putty in colorful plastic eggs selling for $1. Silly Putty was officially unveiled at the International Toy Fair in New York in February 1950. Unfortunately, it failed to generate significant interest, forcing Hodgson to continue to stump for retail outlets on his own.

THE TALK OF THE TOWN

The tipping point for Silly Putty occurred in August 1950, when a reporter for The New Yorker magazine discovered it being sold at a local bookstore and wrote about it in The Talk of the Town section of the August 26th issue. The unexpected publicity resulted in orders for more than 250,000 eggs in just three days!

The initial sales spike was fueled primarily by adults who were interested in the toy as a novelty item. By 1955, the market for the toy had changed dramatically, reflecting its rise in popularity amongst children aged 6-12.

To take advantage of the increased interest in Silly Putty, Hodgson developed a television advertising campaign for it in 1956. With commercials appearing on such popular children’s shows as Captain Kangaroo and The Howdy Doody Show, the campaign was one of the first to exclusively market a toy to children. Early commercials ran for up to one minute and extolled the inherent play value of the toy.

BINNEY & SMITH

After Hodgson passed away in 1976, Binney & Smith, the company behind the Crayola brand, acquired the rights to Silly Putty in 1977. A scant ten years later, sales of the product exceeded 2 million eggs annually. Around 1990, Silly Putty also began to be sold in multiple colors, including a glow-in-the-dark version released in 1991.

Buoyed by this resurgence in the toy’s popularity, the company introduced Changeable Silly Putty in 1995. This version upped the fun quotient by changing color based on the warmth of the user’s hands. Metallic Gold Silly Putty soon followed, just in time to celebrate the toy’s 50th golden anniversary in 2000.

Silly Putty was cemented as a truly classic toy when it was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in Rochester, NY in 2001.

Note: If you buy something using the eBay link in this story, we may earn a small commission. Thank you for supporting independent toy journalism!