Jigsaw puzzles got their start around 1760 in Europe, when mapmakers first pasted maps onto wood and sawed them into pieces. They marketed these “dissected maps” as educational toys for children of affluent families.

During the 1800s the subject matter expanded to encompass nursery rhymes, children’s stories, and current events. Puzzles gained wider distribution as technological advances brought lower costs and better transportation.

Jigsaw puzzles for adults in North America emerged only in the twentieth century. In 1908-09 a craze for puzzles threatened to supplant bridge as the after-dinner entertainment at parties. There was no television or Netflix, but you could rent a jigsaw from a lending library for 5 cents per night or 25 cents a week for your amusement.

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought an even more frantic passion for those perplexing pieces. People who lost their jobs or faced a cutback in their hours could not afford dinner out and a show. They turned to jigsaw puzzles for a fun evening at home. Puzzles offered both a pleasant escape and the satisfaction of being able to solve a problem, unlike the rest of daily life which brought only hard times with no solutions.

At the same time, the housing industry collapse meant there were many skilled workers – machinists, cabinet makers, architects etc. – who brought in some much-needed income by cutting wooden jigsaw puzzles in home workshops, then selling or renting them locally.

Paper box factories idled by the Depression adapted their die-cutting equipment to make inexpensive cardboard puzzles for adults. Soon people were rushing to the newsstands to buy a “Jig of the Week” or a “Picture Puzzle Weekly” for 15 to 25 cents.

Consumer products manufacturers boosted sales by handing out free advertising puzzles to their customers. A recipient could spend hours assembling a picture of a candy bar or a pair of shoes, all the while reinforcing loyalty to that product. One company saw its sales jump 400 percent when it gave a 50-piece puzzle to each purchaser of a 29-cent toothbrush.

During the depths of the Depression in February 1933, New York newspapers reported that ten million new puzzles left the factories each week. With only thirty million households in the U.S. then, that was truly an astounding number.

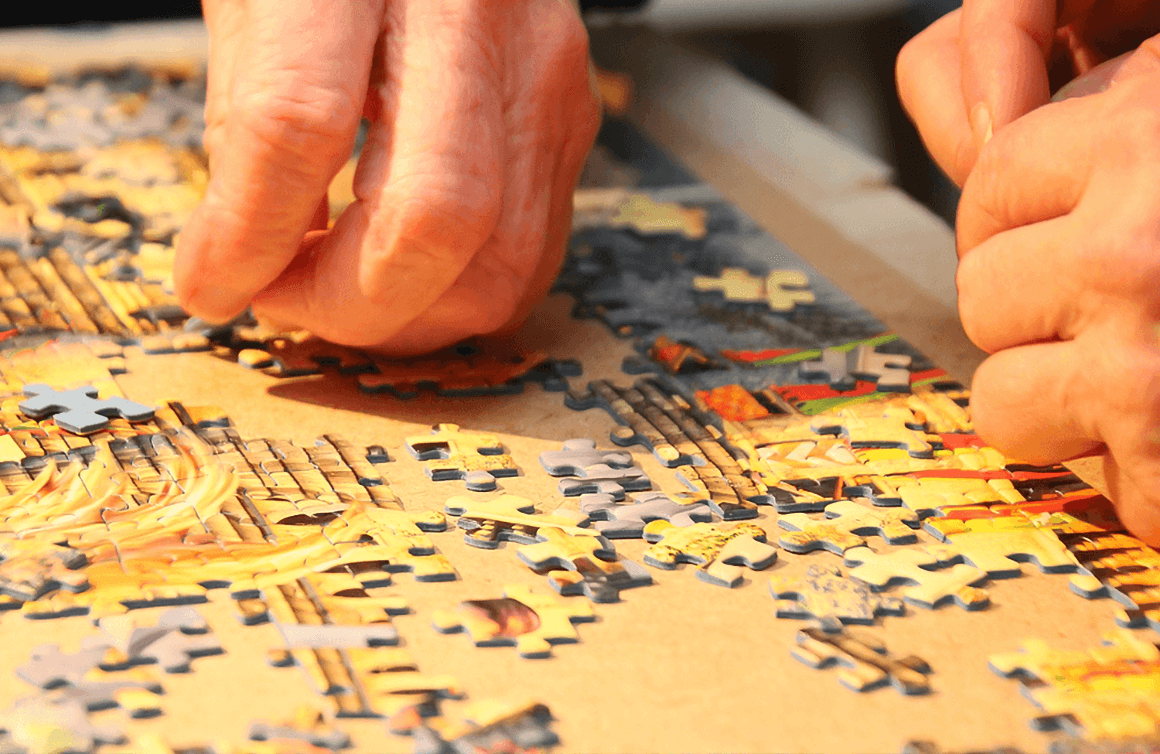

Since World War II cardboard puzzles have predominated, although there are still a few puzzles being exquisitely hand-crafted from wood.

More recently, new technologies have changed the options for puzzle aficionados. Lasers and water jets have brought down the cost of wooden jigsaw puzzles considerably, to the benefit of those who insist on the heft of a thicker piece. Others start their days with an online jigsaw. It doesn’t offer the tactile sensation of an old-fashioned one. But they still get the reward of the completed picture and they never lose a piece.

Modern entertainment media compete for attention today. Yet jigsaw puzzles still appeal. Whether as a solitary activity or a family enterprise, completing a puzzle brings both a sense of accomplishment and an attractive image.

Anne D. Williams is a puzzle historian, collector, published author, and professor. In 2014, The Strong Museum in Rochester, NY acquired the bulk of her personal collection (more than 7,000 puzzles) for its permanent collection.

Note: If you buy something using the eBay link in this story, we may earn a small commission. Thank you for supporting independent toy journalism!