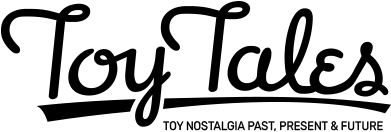

Invented by Ernö Rubik in 1974, The Rubik’s Cube needs no introduction. First called the Magic Cube, the toy really took off in 1980 when Ideal Toy Company changed the puzzle’s name and introduced it to the world. But before we celebrate Rubik’s Cube — possibly one of the greatest toys ever — let’s look at other solitary puzzles that came before the “cubiquitous” cube.

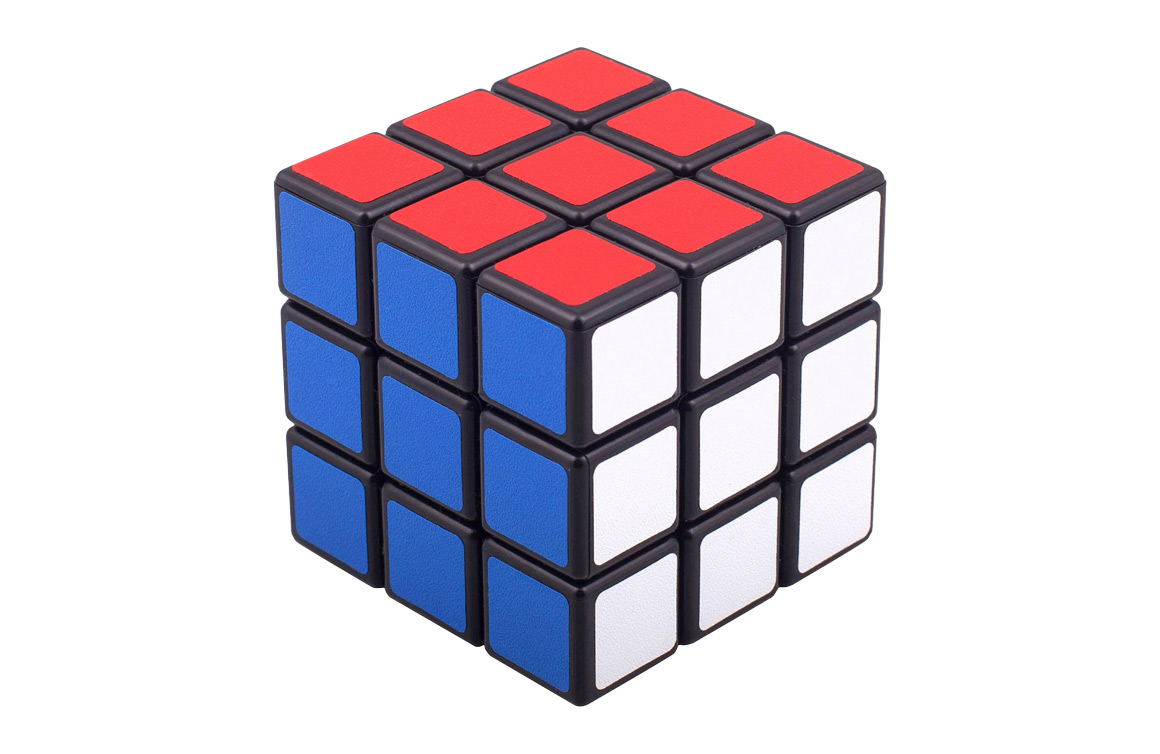

15 Puzzle

An early puzzle, generally known as the 15 puzzle and sometimes as the “slider” puzzle, also involves squares. It was supposedly invented by Mr. Noyes Chapman in Canastota, New York. He is said to have shown friends, as early as 1874, a puzzle consisting of 16 numbered blocks to be arranged in rows of four. The 15 and Rubik’s Cube are both considered “permutation” puzzles — the pieces can be moved around and the goal is to reassemble them into original order. The puzzle has been mathematically analyzed and it can be solved using simple algorithms to move squares into place. 15 puzzles are still widely available both new and on the secondary market.

Pigs in Clover

In the 1880s, toymaker Charles Crandall introduced his large “ball in a maze” puzzle, Pigs in Clover. Simple wood and cardboard challenged a player to guide the wooden marbles (pigs) from the outer rings (clover) to the inner enclosure (the pen, their home). Just difficult enough to perplex the puzzler, the game outsold Crandall’s ability to manufacture it and triggered hundreds of imitations. It was one of the first such run-away toy fads, and cartoonists of the era lampooned the puzzlers for neglecting their work and other responsibilities while they zoned out with the toy.

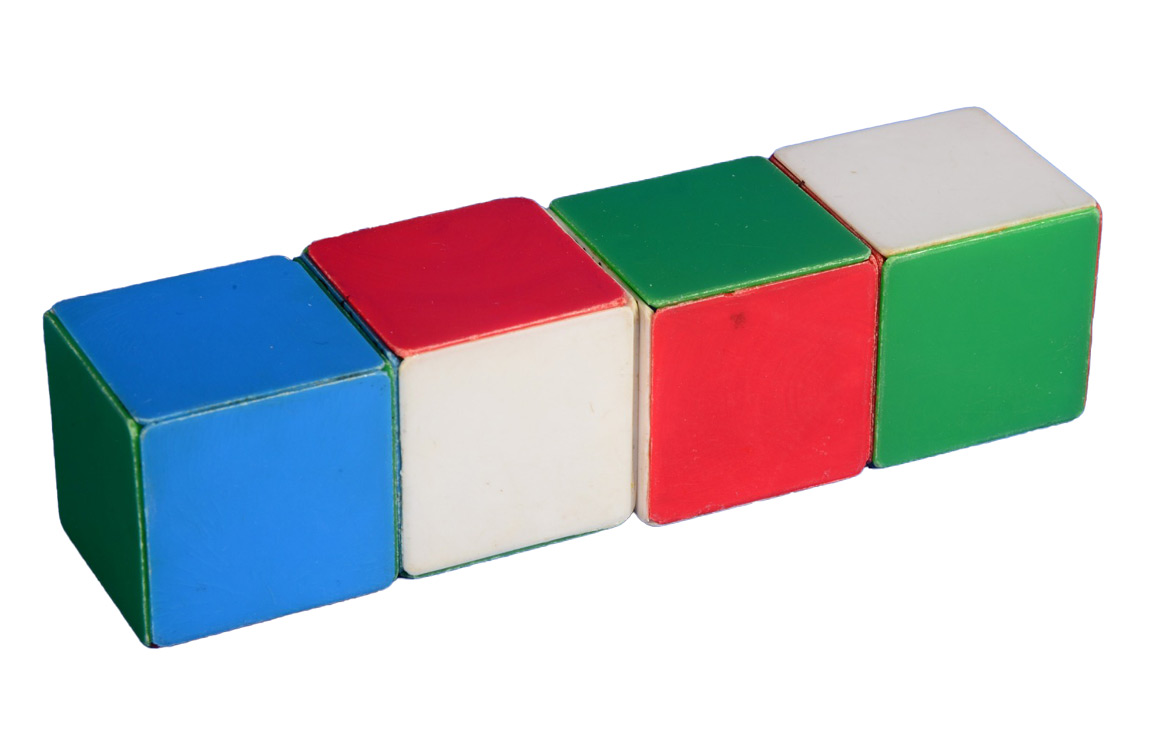

Instant Insanity

Another popular puzzle was first patented in 1900. Produced over the years by many manufacturers and under such names as Devil’s Dice, DamBlocks, Logi-Cubes, and several more, the firm Parker Brothers marketed a set in 1967 called Instant Insanity. The puzzle consists of four separate cubes, each with a side coloured (in this example) red, blue, green, and white. The solution to the puzzle is to stack these cubes in a column so that each side of the stack (front, back, left, and right) shows each of the four colours. Scientists say the problem has a “graph-theoretical” solution — it can be demonstrated by graphs representing edges and vertices. With practice it can be solved in eight moves or less, but trial-and-error takes much longer. This puzzle, too, is still sold.

One might guess that Rubik himself saw each of the puzzles mentioned above before he was inspired to make the cube. Legend says he made it to demonstrate a 3D solid for his students. He was attempting to solve the problem of moving the sides while holding a form together. He didn’t even realize it was a puzzle until he tried to put it back in order. The story, now unscrambled, is history!

Note: If you buy something using the eBay link in this story, we may earn a small commission. Thank you for supporting independent toy journalism!