How did your father’s early interest in mathematics and engineering influence his creation of Spirograph?

Dad’s life and career up to that point had always been rooted in engineering. He was a hugely talented engineer, a master of his profession, and a big part of the family’s engineering business. But he also had an inventive mind, and around the age of 40, he struck out on his own. The family business wasn’t interested in changing direction, and he had all these new, unconventional ideas, so he left.

His first breakthrough was creating a machine for making bicycle springs. After that, he moved into precision engineering for the armaments industry, developing detonators for NATO. It was difficult, highly technical work, and he was very good at it. But he was also a deeply committed pacifist, and eventually he couldn’t reconcile making money from weapons with his conscience. That led to a period of soul-searching. The NATO work paid well, but he wanted something different.

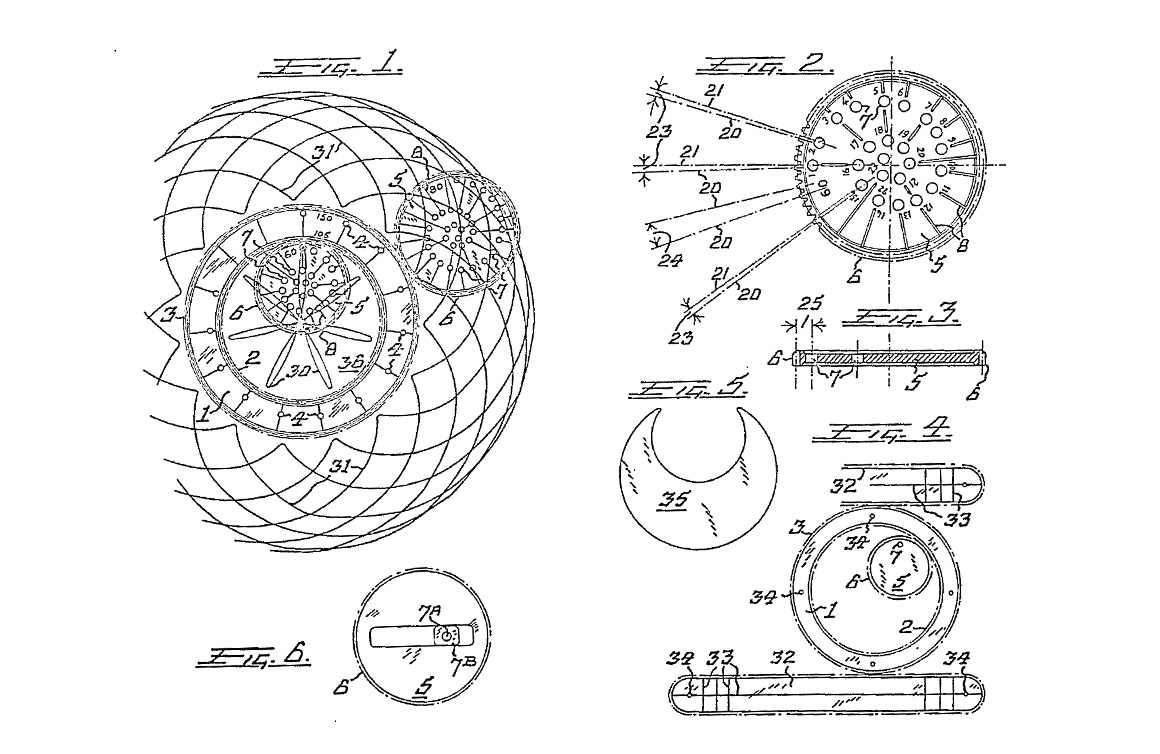

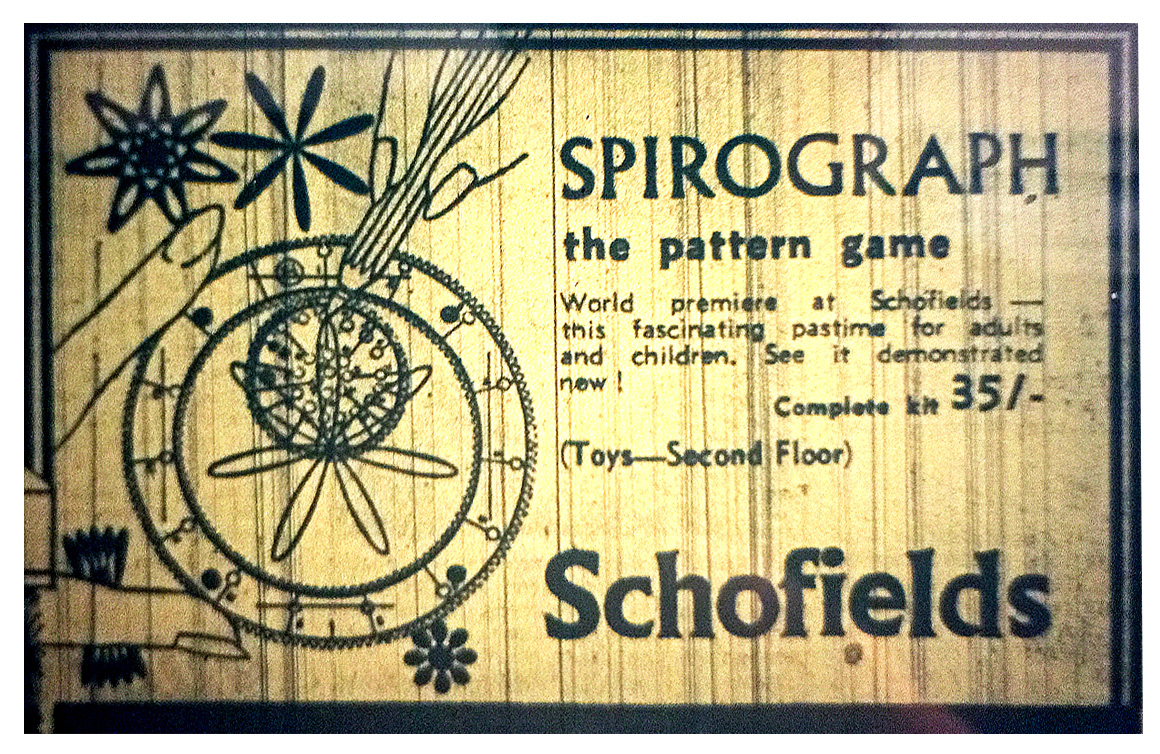

He’d always been fascinated by mathematics and mechanics, especially gear systems. One day, he came across an engraving machine that produced the same kinds of spirals you see on banknotes. That discovery led him to experimenting with contraptions based on the same principles. For a while, he set the idea aside, but one evening while listening to Beethoven, the idea for Spirograph popped into his mind. He realized how simple it could be. At first, he thought it might be helpful for designers or draftsmen, but once he started showing it around, it was clear it had huge appeal as a toy.

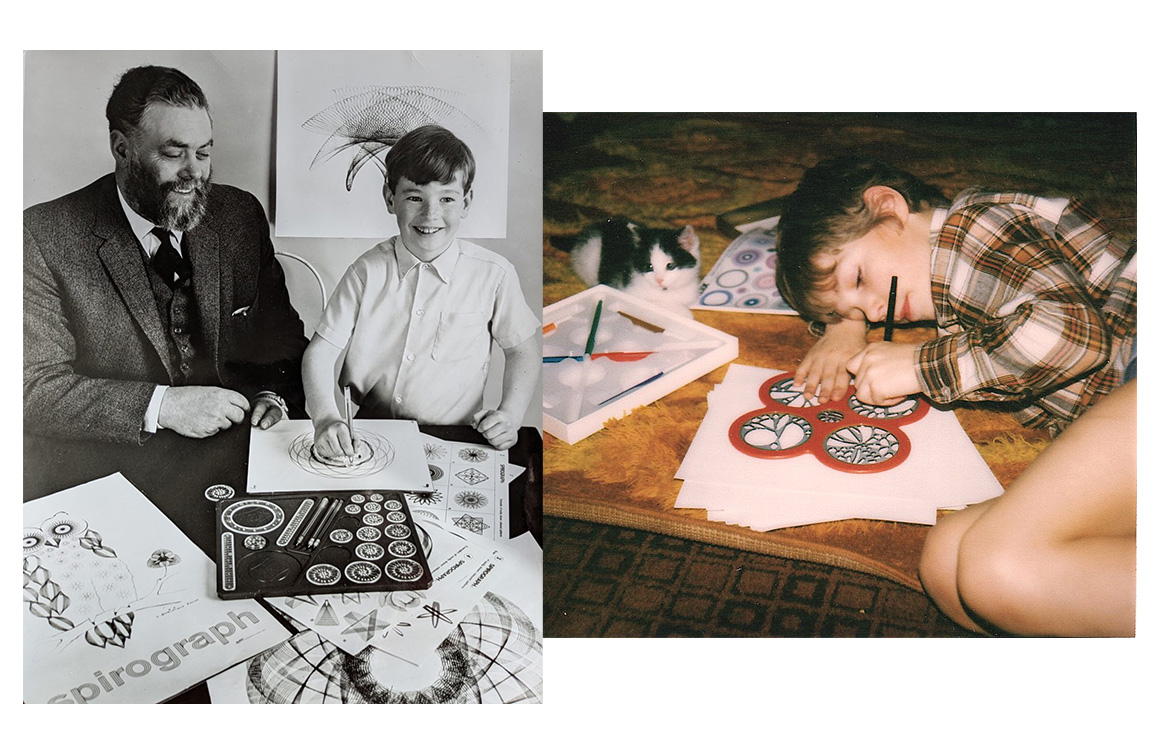

And that’s how he stumbled into the toy industry almost by accident. Spirograph wasn’t designed like a typical toy. It was so precisely made, with the look and feel of a draftsman’s kit. Kids actually loved that aspect of it. It didn’t feel like a throwaway plaything, but something to take pride in.

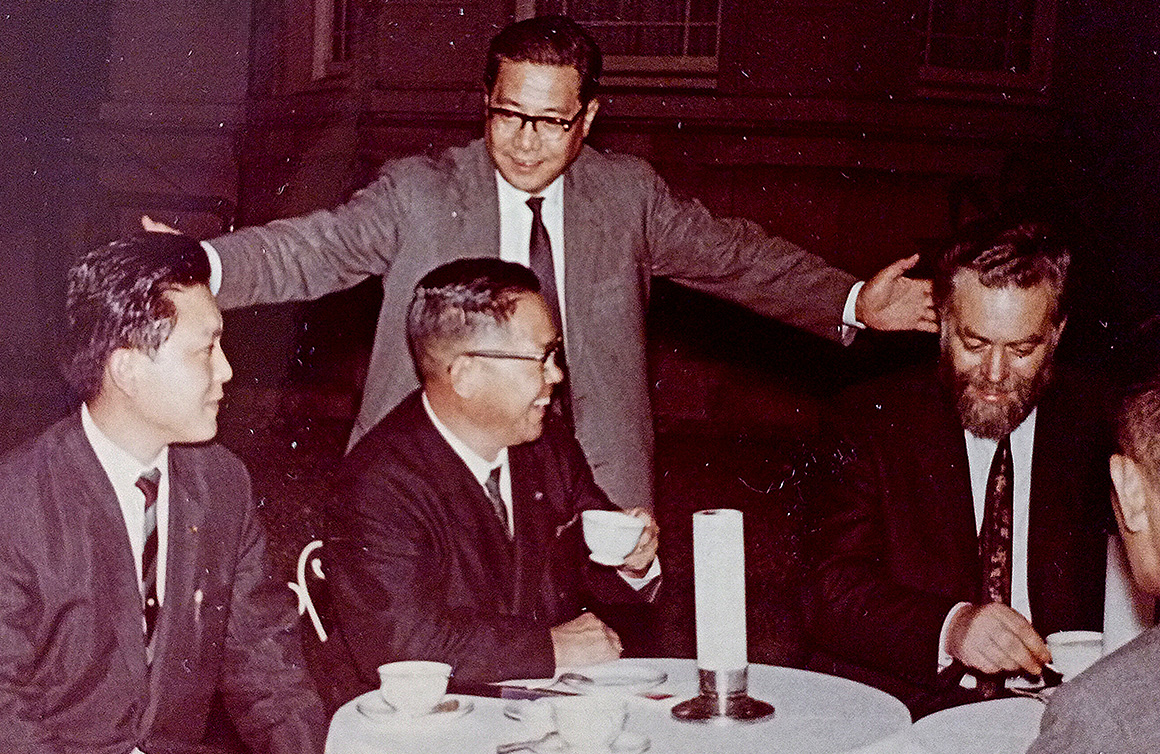

When Spirograph became a hit in Europe, Dad assumed America would be the same. He went over full of confidence, thinking the big toy companies would be competing for it. But meeting after meeting, they all turned him down. They said it was too complicated, that American kids wouldn’t understand it. One executive even told him, “If English kids can get this, you must be educating them better over there than we do here.”

Dad couldn’t believe it. He’d created the best-selling toy in England, and no one in America wanted it. He was ready to give up when he went to one last meeting with Kenner. That’s where he met Joe Steiner, one of the company’s founders. Joe was a maverick, just like Dad, and the two hit it off. Joe admitted he wasn’t sure the toy would work in America, but he liked Dad and decided to take a chance.

Within a year, Spirograph was the number one best-seller in the U.S. American kids loved it just as much as kids everywhere else.

There’s something almost magical about Spirograph. You see the gears, you put in a pen, and suddenly it draws these intricate geometric patterns you never expected. Add in different colours, and the whole thing comes alive.

What makes it so special is the open-endedness. With just a basic set, there are endless possibilities. You try this wheel, that ring, another pen colour, and it’s always something new. That was very much like Dad himself. He loved experimenting, exploring, and trying things out. Spirograph was almost an extension of his personality, a kit that invited everyone else to discover and play in the same way.

Kenner acquired the license to produce Spirograph for the North American market. That kicked off a distinct era of Spiromania. What impact did that success have on Denys’ life?

Once Spirograph took off in America, that was a whole different level. The scale of the U.S. market was unbelievable. Suddenly, they were selling millions of units worldwide. What had started as a small engineering business turned into the company behind the number one toy in America. The money was crazy, the attention was massive, and the whole thing just became a juggernaut.

At that point, Dad stepped back from the day-to-day operations and put managers in charge. What he really wanted to do was invent new toys, because that’s what fascinated him. But once you’ve got the best-selling toy in America, things naturally become more corporate. Dad went along with it, but that side of the business never really excited him. His passion was inventing. That’s where he made his mark, whether it was the machine for bicycle springs, the detonators, or Spirograph itself. Once the company became corporate, the wind went out of his sails. He wasn’t as motivated anymore, which eventually led to him selling.

At the same time, his personal life was changing. He didn’t feel connected to his marriage, and then he met my mom, who was twenty years younger. He courted her until she said yes, and his life took a completely different direction. That’s part of what I explore in the book. There’s the Spirograph story, but there’s also the man behind it, with his own struggles and changes.

In the end, he sold the company at the peak of its success to Palitoy. At that time, British toys were dominating the American market — just like the Beatles topping the charts. I think Americans must have been looking at this little island, wondering, “What’s going on over there?”

Spirograph is a time-tested toy. What is it about the toy that piques the interest of children, even in the digital age?

The magic of Spirograph is that it’s immediately satisfying and a little surprising. When you first look at the gears and holes, you don’t really know what’s going to happen. There’s this sense of anticipation, and then, suddenly, a pattern begins to form. That element of surprise hooks you right away.

When Dad designed the kit, he used his mathematical knowledge to make really thoughtful choices about the gear sizes and the number of teeth on each wheel. Those decisions weren’t random; they were calculated to produce the greatest variety of patterns. What you end up with is this clever little box of tricks. Swap in a different gear and you get something completely new. Kids love that exploratory side of it. You pick it up, put your pen in, and start creating. There’s no learning curve, no barrier to entry.

And it’s universal. Wherever it went, kids immediately understood how to use it. There were no cultural barriers, because the joy of making beautiful patterns is something everyone can relate to. Even when American toy companies didn’t believe in it, the kids did. They embraced it wholeheartedly.

Another part of its appeal is how calming it is. These days, we’d call it mindfulness. The modern world can be overstimulating, but Spirograph pulls your attention in gently. You focus on following the wheel, and it calms the mind without tiring you out. At the end, you’ve got this beautiful pattern you’ve made yourself.

In fact, Dad once marketed Spirograph as a “nerve soother for the stressed executive.” The idea was that businesspeople could use it between meetings to unwind. It sounds funny, but there’s truth in it. Gandhi did something similar—he always carried a spinning wheel with him. Even during high-powered meetings, he would pause and spin cotton as a way of recentring himself. It was his way of balancing focus and calm. Spirograph works like that. It gives your mind something creative and gentle to play with, so you can reset.

And sometimes, it’s as simple as keeping kids occupied. One man told Dad he bought a set because a friend swore it would keep his children quiet, and it did. That’s the beauty of it: it’s fun, it’s soothing, it’s creative, and it still fascinates kids today.

Denys Fisher Toys went on to produce other classics such as Stickle Bricks and Cyclex. As an engineer, do you think he saw play in a different light?

As for Dad’s approach to play, yes, being an engineer really shaped how he saw it. He believed in children’s potential. He could have made Spirograph easier — like putting it in a frame so it never slipped—but he felt that would take the fun away. He wanted it to be a bit of a challenge.

He was also an absolute stickler for quality. The original sets were made to a level of precision far beyond what was necessary, but he believed that cutting corners would have compromised the toy’s success. The gears had to move smoothly. The plastic had to feel right. Everything needed to be exact. That was his engineering ethos: don’t make it cheap, make it perfect. And I think that’s one of the reasons people loved it.

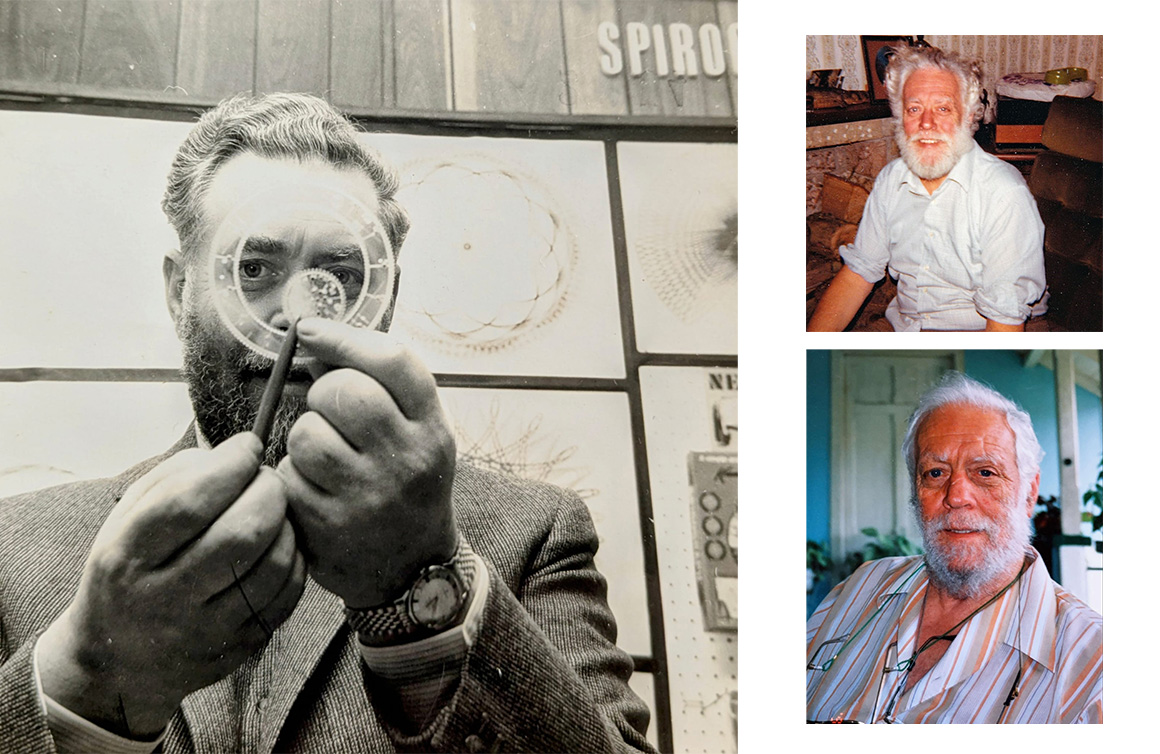

You’ve documented your dad’s legacy online and in a biography—what motivated you to share his story, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

A few years ago, I met a writer named Charlotte Bradman. When I mentioned that my dad had invented Spirograph, she couldn’t believe it. She said she’d spent half her childhood playing with it and had been absolutely obsessed. The more we talked about Dad—his life, his career, his personality—the more she said, “This has to be a book. His story is just too fascinating not to tell.”

And she was right. I’d always known my dad lived an interesting life, but seeing that enthusiasm from someone else really made me realize how important it was to share it. Of course, writing a proper biography is a huge amount of work, but I asked myself: what’s my motivation? For me, it wasn’t just about retelling the Spirograph story. It was about exploring who Dad was as a person. The curiosity, the love of life, the constant quest for wisdom. He was an inventor, yes, but more than that, he was someone who was endlessly fascinated by the mystery of life itself.

In the book, I tried to capture both sides: the practical and the philosophical. There’s the story of how he built businesses, the lessons he learned, and the unusual ideas he had about life and work. But there’s also the more personal side—what he meant to me, how his curiosity shaped my own outlook, and the many conversations we shared. He was such a positive influence. I remember times when just talking to him would completely change someone’s perspective. He had that kind of effect on people.

What I hope readers take away is a sense of his example. He never took life too seriously. He saw it as something creative, something we can shape for ourselves. And there’s something in his story for everyone. If you’re simply a Spirograph fan, you’ll enjoy learning how it all came about. But if you’re looking for more, you’ll also find lessons on creativity, resilience, business, philosophy, and even humour—because he was genuinely funny, too. I hope that readers come away inspired, entertained, and maybe even a little changed, just like so many people who met him in person.

What do you believe is the most enduring part of your father’s legacy—both as an inventor and as a person?

It’s his example of who he was as a person. Obviously, he wasn’t perfect, but when you step back and look at the bigger picture, he was a remarkable character.

What really stands out for me is his pacifism. He was almost allergic to conflict. He had presence, and he was a strong and influential figure, but never through force. His influence came through the strength of his character, his integrity, and his humanity.

He had this deep belief in people’s potential. That’s why it feels so fitting that he became a toy inventor. Once he stumbled into that world, he realized he’d found something that let him channel all that—his creativity, his optimism, his love of opening up possibilities for others. He always said, “When I landed in the toy industry, I knew I’d landed on something good.”

Toys gave him a way to inspire people, to unlock creativity, and to open up new worlds for children. That mix of inventiveness, integrity, and humanity is his true legacy.

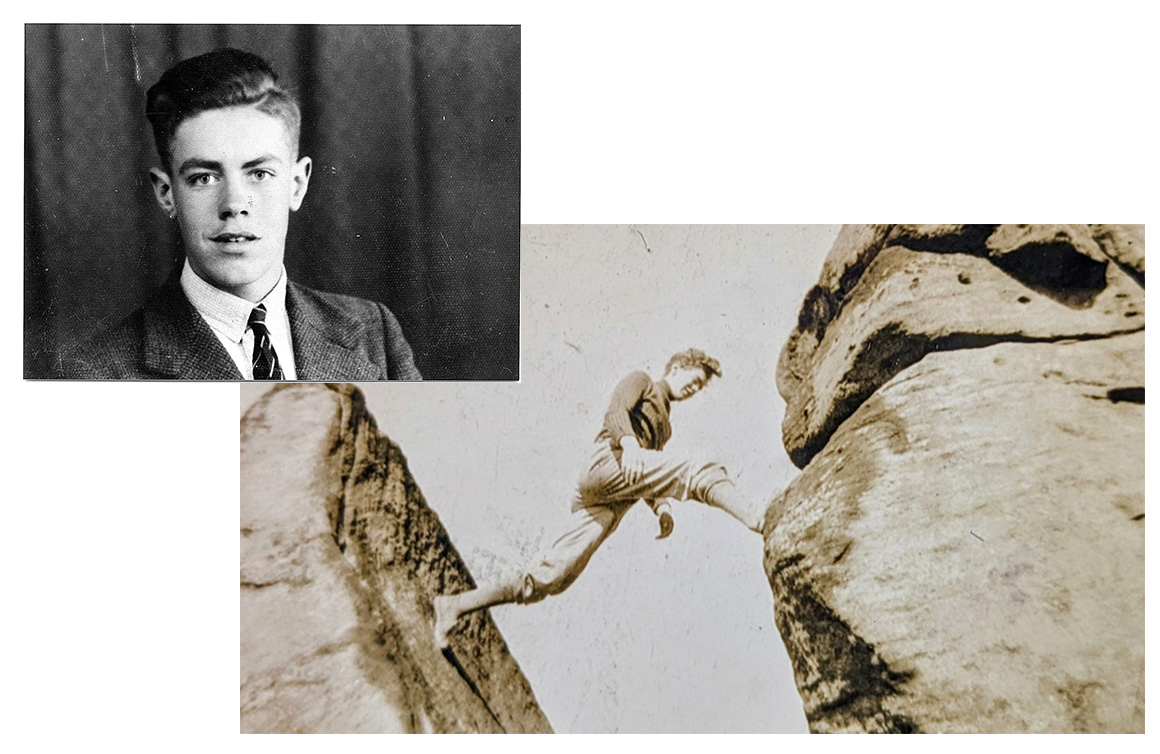

He was unique, but in some ways, this uniqueness stemmed from his upbringing. His family was eccentric—full of inventors, social reformers, and free thinkers. Dad grew up in a railway carriage in a field his father had bought. They just decided, “Well, we’ll live here until we come up with something better.” That kind of free, self-made attitude shaped who he became.

He wasn’t really raised in religion, though the family had Quaker roots. But he was raised to think for himself, to be creative, and to treat life as something you could shape.

That carried into his work. He had this wonderful ability not to overthink. He’d say, “If you want to do something, make a start. You’ll figure the rest out along the way.” And that’s how he lived. He had enough skill and confidence to trust himself, even when he left the family business with a young family to support. It was hard work, but he made it stick.

And when Spirograph took off, he didn’t cling to the old path. The engineering business became a toy business. That was Dad: life was an adventure, and he’d rather have been poor and have an adventure than be rich and bored.

Writing about a parent can be tricky. It’s easy to turn them into saints or villains, depending on how you feel. I wanted to strike a balance.

There was a moment when I was about 11 that changed everything. We lost everything. Dad got caught up in a legal dispute over a toy concept that overlapped with Spirograph, and he didn’t handle it well. Usually, he was measured, but this time he dug in, and it cost us dearly. We went from living in a mansion in Scotland to moving into a friend’s bungalow on a farm. That was a huge blow, even for someone as irrepressible as Dad. But it also revealed another side of the story. My mum really stepped up. She was practical and grounded in ways he wasn’t, and together, they found a way forward.

And Dad, true to form, eventually bounced back. He got fit again, walked the hills, reconnected with nature, and rebuilt his work doing consultancy for major toy companies. For him, life was still an adventure. He’d say, “Okay, we’ve lost everything, but the sun’s shining, I’m on top of a mountain—who’s living better than me today?”

That’s the heart of it. Yes, Spirograph is the invention people remember, but his real legacy is broader. It’s that adventurous spirit, that belief in people, and that sense of humanity that came through in everything he did.

Learn more about the life of Denys Fisher.