Tell us about the Changnon family.

The Changnon family, in relation to the museum, is my immediate family. That’s who I thought of when developing the museum. I wanted it to be an opportunity to showcase the collection I’ve amassed over my lifetime, but also to honour the family who has accepted and loved me for who I am.

I envision the collection growing beyond just items from my own childhood or things I’ve collected myself. I have two younger siblings and my parents, and we all collect or are passionate about different things. I thought it would be a great opportunity, especially at the beginning, to showcase different parts of what makes my family unique.

For example, my grandfather on my father’s side collected model trains. We don’t have many of those in the family anymore, as they were divided among his children, but I like to think my collecting passion came from him. That sense of collecting was always present.

My parents’ collecting looks very different from mine. Over the years, they’ve collected mid-century modern furniture, and their home in the Chicago suburbs feels like a museum in its own right. Even the exterior has a mid-century modern feel, and when you walk inside, it’s like stepping into a time capsule.

My siblings collect as well. My brother works in film and television, and over the years, he’s collected memorabilia from the productions he’s worked on, including cameras, posters, records, and various items related to those projects.

For me, though, the focus has always been toys. Growing up, especially during difficult periods of my childhood, toys and the stories around them gave me comfort and a sense that I wasn’t alone. As a child, it’s easy to feel isolated, and sometimes you don’t want to turn to family. For me, toys were companions, teachers, and sometimes lifelines.

The museum reflects not only what I’ve collected and what my family has collected and supported me in collecting, but also storytelling, history, and creativity.

What inspired the creation of The Changnon Family Museum of Toys and Collectibles?

My collecting started very personally when I was a child and continued through young adulthood and into my thirties. It was never something I approached with the idea of building a museum. It was deeply personal.

In particular, the American Girl brand, dolls and stories rooted in different moments of American history, played an important role for me growing up. Those characters and their stories helped me make sense of my own life and the challenges I was facing. I am a survivor of childhood abuse, and while the experiences of those characters were different from mine, the emotions they navigated were very similar. Many of them dealt with loss, family change, or major transitions. That emotional resonance helped me understand what was happening in my own life.

As a child, I wasn’t collecting with intention or foresight. I collected these items because they meant something to me. Through the stories and characters, I created a sense of friendship and connection. Having a doll, a plush, or a book offered comfort and grounding when I needed it.

The turning point came in 2021, during the pandemic. At the time, I was living in Nashville, Tennessee, away from my family. I had already built a sizable collection of American Girl and Pleasant Company products, including dolls, books, accessories, and related materials. I decided to share the collection online with family and close friends to stay connected and have something joyful to focus on.

When I launched what would become the museum online, I quickly realized there was a real hunger for connection, nostalgia, and thoughtful storytelling about the toys of our childhood. What began as something personal suddenly became something public.

The museum launched as a digital platform and quickly gained momentum. People responded to the care, intention, and storytelling behind the collection. That’s when I realized there was something meaningful here, not just for toy collectors, but for American Girl fans and researchers who wanted to learn more.

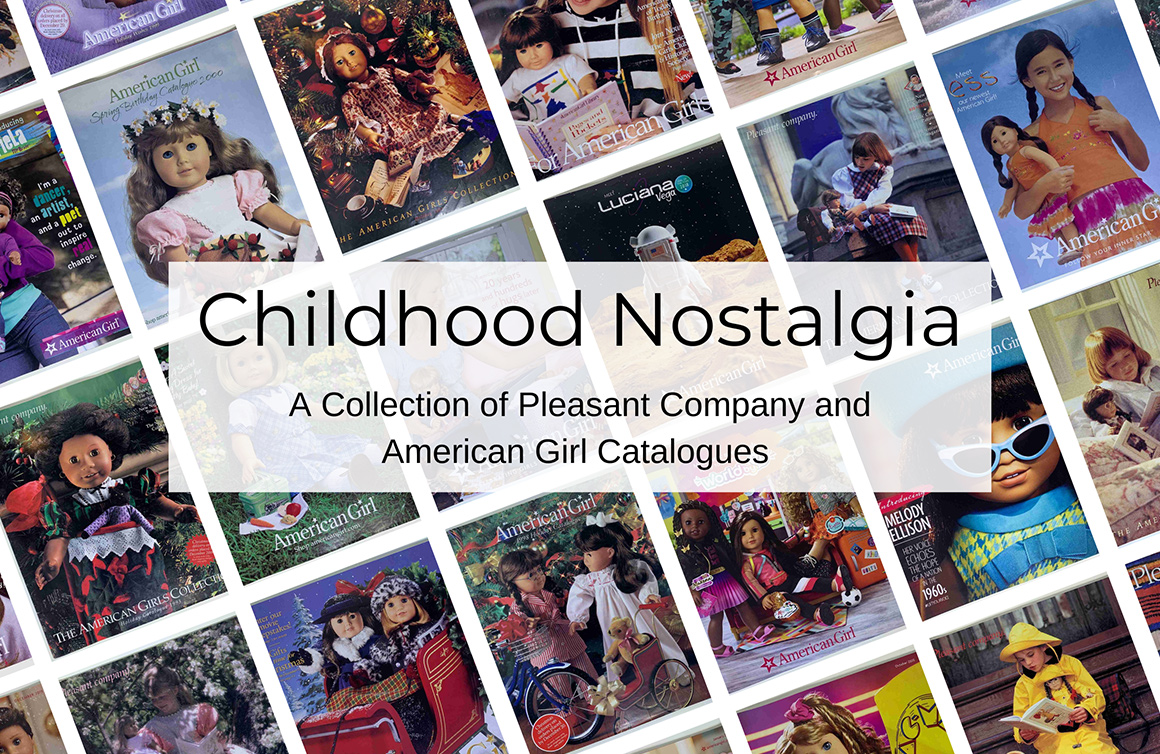

Today, the collection includes more than 5,000 objects. These aren’t limited to dolls, clothing, or accessories. They also include paper materials such as catalogs, which were especially significant to the American Girl brand.

One of my favourite exhibits focused on those catalogs. Many people remember receiving them in the mail, flipping through stiff pages, circling favourite items, and returning to them again and again. Hearing those shared memories has been incredibly meaningful.

That exhibit required significant work. As a one-person museum, scanning and cataloguing the materials was time-consuming, but I wanted visitors to be able to engage deeply. Within the first three months, the site received more than 100,000 visitors. That was the moment I knew there was truly something here.

Since then, the archive has continued to grow. While we’re not currently adding new catalogue scans, the exhibit remains available, and researchers continue to reach out. Some travel to the DC area to view materials in person for dissertations, academic papers, or research projects. Supporting that work has been one of the most rewarding aspects of building the museum.

What challenges come with a digital-first museum?

One of the biggest challenges of being a digital-first museum is interpretation.

In a physical museum, visitors can experience an object in space. Online, that experience is much harder to replicate. You’re often limited to a photograph with accompanying text. Telling a story clearly and emotionally becomes more challenging. Because of that, every element has to work harder. The images, captions, and labels all need to convey context, meaning, and feeling in a limited space.

I come from a background in marketing and communications, so I’m always weighing decisions as I curate an exhibit. I’ll ask myself whether to invest resources in professional photography or to use them to acquire additional items for the collection. Writing is also a significant part of that work. Each caption and label has to be thoughtful so the object doesn’t feel disconnected on screen.

Preservation and storage are another major challenge. Because the collection is so large, I maintain an off-site storage facility. Proper storage is essential, especially for dolls. I’ve consulted with museums and historical societies about best practices. For example, dolls are better stored standing rather than lying down, as internal face mechanisms can sink over time.

Documenting where everything is can be difficult as a one-person operation. I’ve had moments where I thought I had two of a particular doll from 1987, only to realize I had five, simply because I hadn’t properly documented where they were stored.

There’s also a deeply personal side to the collection. In what I call my office, or the doll room, I keep a small number of items that aren’t in storage because they hold special meaning for me. One example is Kirsten, the American Girl character from 1854. I have three versions of her: an original doll from 1986, signed by the company’s founder; a newer re-release; and the one I had as a child. That childhood doll was a gift from my younger brother and is signed by the author of the Kirsten books.

Seeing those dolls together highlights both physical changes in manufacturing and the emotional layers tied to them. When these objects are displayed publicly, that emotional connection extends to visitors. Parents often share them with their own children, and many become visibly emotional when holding them again.

How do you envision the museum evolving over the next few years?

About five years ago, the museum was entirely digital. It focused on catalogues and the celebration of American Girl’s historical characters. At the time, that format felt like the right place to begin.

What I’ve learned since then, especially being based in the Washington, DC area, is that there’s a strong desire to experience this material in person. That led me to connect with local libraries, where we’ve hosted temporary pop-up exhibits. These are typically one-day exhibits, simply because space and resources are limited.

Those pop-ups have been incredibly instructive. My first one featured the first seven Pleasant Company characters and their school accessories. Feedback from visitors led to a holiday-themed exhibit, and both pop-ups were free and fully booked within days.

As a result, the library has invited me to do additional exhibits, and I’ve begun connecting with museums across the country interested in adapting these into longer-term or travelling exhibitions. I’m currently in conversation with institutions in Virginia, Wisconsin, and Las Vegas about what that could look like.

Doing these smaller exhibits has helped me understand what resonates most. There’s a strong response to the early characters from the 1980s and 1990s. Watching visitors’ reactions and hearing their memories has helped shape how I think about future exhibits.

The museum will always maintain a strong digital presence, but expanding into in-person experiences has been incredibly rewarding. It allows people to connect with these objects and stories more tangibly.

What do you hope future generations will understand about play through this collection?

I hope future generations understand that play is not trivial. Play teaches empathy. It teaches us how to imagine different lives, different histories, and different futures. Through American Girl in particular, children can practise being brave, kind, curious, and resilient.

I hope future generations see that toys reflect the world around us, our values, our struggles, and our hopes. When you look at a toy from the past, you’re not just seeing plastic or fabric. You’re seeing what society believed children should learn and grow into at that moment in time.

More than anything, I hope future generations understand that play has the power to heal, to teach, and to connect us across time. That’s exactly what it did for me, and I hope this collection helps carry that understanding forward.

Learn more about The Changnon Family Museum of Toys and Collectibles.